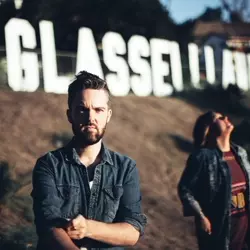

Jordie Lane & The Sleepers

Jordie Lane & The SleepersJordie Lane and Clare Reynolds walk to the centre of the open roof of The Music. The sun is warm and the first notes of Black Diamond bounce off the pillars and well up into the city sky. A rich, dripping harmonisation, with twangs of brooding alt-country and a hint of blues melancholy, but yet, sitting there in the sun enjoying such an intimate moment between artist and an audience of two, you can’t help but feel an overwhelming sense of contentment.

This is the experience of Lane’s long awaited LP GLASSELLLAND, pieced together by his friend and producer Reynolds while the two were living in LA. “Los Angeles is this big, scary, concrete city but it’s so open in terms of how you wanna express yourself,” he explains, taking a drag from a rollie cigarette. “Whatever you want to be, any kind of music, everyone’s like ‘sweet!’ and there’s a niche for everything. You find your people,” Reynolds smiles as she shields her eyes.

Fresh off the plane from the US, the two are a little sleepy, a little dishevelled. Lane is explaining the story behind the album’s first single Frederick Steele McNeil Ferguson (try saying that ten times), which was written about his grandfather. “That was my great grandfather’s real name, but they just called him Fergie. So that’s easier – I should have just called the song ‘Fergie’,” he jokes. “My dad had told me that [my grandfather] lied about his age so that he could go and fight in WWI, he was 16... I just started singing that name over and over again and it just, I dunno. Being so disconnected from my past but knowing that that’s embedded in us, I was just thinking about how – now I am jetlagged,” he sighs, brows raised. “Waddya even call it?

“Los Angeles is this big, scary, concrete city but it’s so open in terms of how you wanna express yourself.”

“Like the past being in your blood?” Reynolds offers. “Ancestral sin! This theory that those things do get passed through generations," Lane picks up. "So the trauma that he’s been through or whatever would potentially pass through to future generations... Really it’s just a song to remember the good of the situation you’re in, that I’m not having to go off and fight in a war.”

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

Reynolds and Lane, exhausted from three years of touring, went in search of a quiet space to record an album in north east LA. They found a dilapidated bungalow in Glassell Park and set up shop. “It was part lounge room, part kitchen, didn’t even have a door to the bedroom, so there wasn’t much space. So we build little partitions and little vocal booths in there, literally out of chairs and ladders and blankets and pillows and things like that,” Lane laughs. “The beginning of making this album was really hard. We’d been touring pretty solid for three years and we hadn’t really sat down to be in this really vulnerable state and really listen to yourself... Getting out of bed at 4pm in the afternoon going, ‘I don’t know what to do.’”

Inspiration came, and seemed to keep on coming – not from waves of genius, but from the mistakes the two made along the way. Undertaking the production of the LP solo in spaces not set up for recording – “we went and bought a bunch of equipment and it sort of stayed unopened in the box for like a month or two, I was scared!” - they found it was better to use their environment rather than fight against it. “We used a lot of sounds that were laying around; in the kitchen, pots and pans, cheese grater, and one day we came home with coffee cups and pencils,” Reynolds remembers. “The last song we recorded, In Dreams Of War, I was trying to do the backing vocals and this cricket would start at 9pm every night and we’re like ‘ah man, it’s done it again!’ Jordie would knock the wall and it would stop for 30 seconds and I’d try to get my take in, and then it would start again. Then we’re like ‘it’s nearly in tune with us, let’s just keep it!' At the end of the song you can hear the cricket. It’s a big credit, we forgot to put him in there!” she realises with a giggle.

Lee Ferris’ artwork for GLASSELLLAND vividly portrays the music’s subject matter – most notably, America, Won’t You Make My Dreams Come True? in which houses are replaced by guns. “It’s a bit frustrating. Some of the most left wing thinkers, they all don’t have much of an idea of hope of how to take guns away from the American landscape,” Lane muses. Reynolds agrees: “There were so many moments where we’d come home feeling like ‘I felt really scared today in this public place’... I feel lucky to be Australian in these times.”