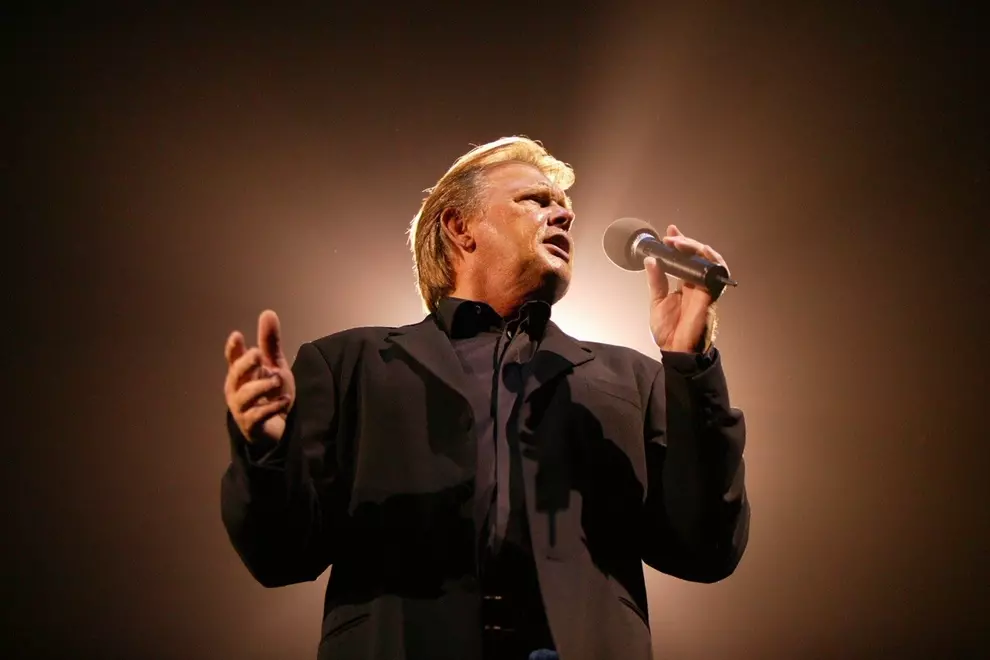

John Farnham

John Farnham“When you start making a film and recording life, life happens.”

So says Poppy Stockell, the director and co-writer of John Farnham: Finding The Voice.

Stockell was thrown some unfortunate curveballs during the making of the documentary, which opens in cinemas on May 18. First, Farnham’s manager of more than 40 years and his best mate, Glenn Wheatley, died suddenly. And then the singer was diagnosed with cancer. As his son Robert notes in the film: “It’s a sick joke – The Voice gets mouth cancer.”

The tragic twists rocked Stockell, though she says, “As a documentary maker, you deal with whatever it is that’s in front of you.

“Losing Glenn was an incredible tragedy. But that gave us more fuel to realise this film. It was his huge wish to see John’s life celebrated on the big screen.”

When Stockell was engaged to make her first music documentary, her initial aim was simple:

“Just not fucking up.”

“It’s such an incredibly important story,” she explains. “A huge story of epic, Greek-hero proportions. And I wanted it to be that. I wanted it to be big and emotional.

“Lots of people have been approached over the years – band members and collaborators, the Farnham family, the Wheatley family and all the musicians. They’re an incredibly cohesive, loyal bunch. Convincing them all to trust me with the story was something I took very seriously.”

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

Stockell discovered more depth in Farnham’s story than she expected. “You think it [his career] was probably tough, but I had no idea how tough it was. I guess great artists are great because of their interpretation of human emotional experience. And John really nails human emotion.”

After extensive research, Stockell was struck by the fact that Farnham’s life fitted the template of the hero’s journey, with the call to adventure, meeting with the mentor, the ordeal and reward, followed by the road back and resurrection.

“It’s like Heracles, Perseus or Achilles; all these Greek myths and legends. John’s life just sat in that framework so epically. And that’s what I wanted to do.

“Elton John has been celebrated with Rocketman, and I absolutely wanted John’s life to be celebrated in a really big way.”

The documentary depicts Farnham’s remarkable relationship with the Australian public. “John’s life, his story, is our story,” Stockell believes. “Sadie was the biggest-selling Australian single of the ’60s and I think that says more about us than him.”

“A lot of rock stars will often have disdain for their audience or they’re too arrogant to appreciate that the audience have put them there,” Stockell continues.

“I don’t think at any point in John’s career did he forget who his audience was.”

The documentary also shows there are no real “solo” acts. As Richard Marx observes, in an industry not noted for its loyalty and compassion, Farnham and Wheatley were like brothers. They never had a contract but were together until the manager’s death (Wheatley’s wife, Gaynor, is now Farnham’s co-manager).

After the record-breaking success of Whispering Jack – the first local album to sell one million copies in Australia – Farnham said of Wheatley, “He put his money where my mouth is”, acknowledging that the manager mortgaged his house to pay for the record, and then started his own label when every major record company passed on the album.

Later, Farnham would return the favour, standing by Wheatley when he was jailed for tax fraud.

The documentary focuses on the key relationships in Farnham’s life and career, relationships noteworthy for their loyalty and longevity.

The film starts with vision of a conservative Australia in the 1960s. “It was like we were sleepwalking,” Olivia Newton-John reflects.

“Music woke us up,” Jimmy Barnes says. “The big question was, who was going to be our big star, who were we going to worship?”

Farnham was discovered by Darryl Sambell, a former hairdresser who heard him singing at a gig in Cohuna, a small town in country Victoria.

Thin, bearded and balding – he would later be dubbed Rasputin by Jillian Farnham – Sambell became Farnham’s first manager. His aim was simple: To make Johnny Farnham as big as butter.

Sambell found Sadie, and Farnham quit his job, as an apprentice plumber, two days before the single was released. It became Australia’s biggest-selling single ever – a title it held until Up There Cazaly came along 12 years later.

The manager is criticised in the documentary for failing to break Farnham internationally (EMI in the UK reportedly said, “We’ve got Cliff Richard, we don’t need this guy”), but he did help the singer become a pop sensation at home, winning the King of Pop title five times between 1969 and 1973, with the crown becoming known as “Darryl’s Hat”.

Ian “Molly” Meldrum, a friend of both men, called Sambell “a genius manager”.

“Darryl was brilliant, creatively and artistically. He gave John Farnham the grounding that ensured he has survived until this day. But Darryl was also obsessive and possessive and this became stifling.”

Sambell is the villain of the piece, with Jill Farnham saying he “wasn’t a nice man, [he was] evil actually”.

Jill – a dancer who met Farnham when they both appeared in the stage musical Charlie Girl – believes Sambell tried to sabotage their relationship because he was in love with Farnham.

Sambell was the best man at their wedding, finishing his speech by saying, “John and Jill are off on their honeymoon. I wish them the best of luck and while they’re away I’m going to work on their divorce.”

“Darryl tried everything he could to destroy the relationship,” Gaynor Wheatley says. “But he only made it stronger.”

John and Jill celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary this year.

After nine years together, Farnham and Sambell’s relationship dissolved at the start of 1976, a seismic shift so significant, the banner poster of The Age newspaper said simply: Farnham Sambell Split.

Six months later, Sambell called Farnham to wish him a happy birthday. It was the last time they spoke. Sambell died of lung cancer in 2001, aged 55.

Jill stood by her husband as his career floundered in the late ’70s. “We were on the bones of our arse,” she recalls.

Glenn Wheatley rescued the singer from the leagues club circuit, told him to drop the Johnny moniker to show he was now grown-up and serious, and placed him in Little River Band. He made three albums but felt creatively stifled, though his time in the band did provide Playing To Win – his “coming-of-age song”, according to Gaynor Wheatley.

“It was so good,” Stockell says of the 1984 single. “It was where he threw off the gloves in that ice hockey moment and said, ‘Right, bring it to me!’”

Wheatley tried unsuccessfully to get Quincy Jones to produce Whispering Jack, which was released just three months after Farnham’s final album with LRB. The job ended up going to Ross Fraser, who had been LRB’s stage manager.

While trying to source songs for the album, Farnham and Fraser came across a demo of We Built This City, co-written by Bernie Taupin. “Ross and I thought, ‘Wow, pop anthem’,” remembers keyboards player David Hirschfelder of the song that would become a US #1 for Starship. “But John thought it was too twee.”

Fraser became Farnham’s most significant musical collaborator, producing all of his subsequent albums, aside from his Christmas record with Olivia Newton-John.

In one of her final interviews, ONJ talks about her love for Farnham in Finding The Voice. “He’s my favourite singer,” she reveals. “He’s The Voice, right.”

“Olivia was obviously very sick, and her voice is very fragile,” Stockell says. “But she really wanted to tell John and Australia how much she loved him.”

Stockell hopes that fans see the documentary on the big screen as she tried to replicate the excitement of a Farnham gig.

“A lot of people talk about the energy of being at a John show, the energy going back and forth from the stage – this incredible connection, an almost spiritual experience of audience and musician coming together.

“That really moved me a lot and I wanted that to be reflected in the documentary, which is why I’m so happy it’s getting a cinema release, because it’s a communal experience, like a John show.

“He always said that he did all of the other stuff just to be able to go and sing live. That’s why he did it all – all of it was to get up on stage.”

John Farnham: Finding The Voice arrives in cinemas this Thursday, 18 May.