Our relationship with the machines we create has always been vexed, (from dark Satanic mills to facial recognition and the looming spectre of AI), and just as society at large has wrestled with the double edge of tech so too have artists. However, few of us have ever danced with a robot.

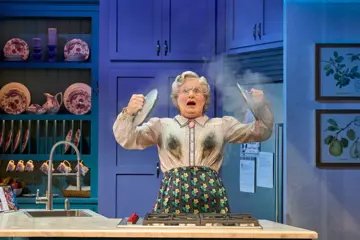

When Taiwanese dancer and inventor Huang Yi takes to the stage with his robot partner Kuka at the Seymour Centre this week the man/machine relationship will be stretched beyond sci-fi and into something not only beautiful but emotional.

Once we recover from the sheer novelty of it Huang Yi & Kuka promises to leads us into the half-lit terrain where human frailty and robot precision merge and, for a while at least, become indistinguishable. As Huang recalls, "When I began this project, it was just a simple dream — to dance with a robot. However, through the process, and by watching the rehearsal footage, I discovered that my own unconscious feelings were being revealed."

"When all those rules need to be exact we really need to identify what rules are 'fair'. In fact, the root of this problem is that fundamentally there is no fairness in the world."

Indeed, Huang now regards Kuka as something of a mirror. "I've always felt that no one really understands anyone else and that humans are really always alone," he explains. "But when I'm dancing with Kuka, because it often copies my actions, it feels like dancing with myself. Facing another object that mirrors your own feelings is difficult to describe, especially when that 'other' is not human."

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

If we were dealing with the usual '100% human' landscape of contemporary dance all this talk of emotion would be par for the course. Within the context of Huang Yi & Kuka though, it takes on a philosophically denser quality. "Fundamentally, Kuka is a calm precise program executor, similar to a piano," Huang elaborates. "But Kuka also very precisely executes the given personality, character and emotional details, and how we humans live together with such properties. So, every time I perform this piece, I discover new things."

The question here is fundamental: what, if anything is the effective difference between the so-called 'real' and it's brilliantly detailed copy? For many this uneasy notion sits at the heart of their concerns about technology and, in particular, about AI.

Huang Yi is more than ready to dive into this discussion. "To morally define machinery and technology is very important," he declares. "Humans have emotions and often make mistakes. Humans need emotional space but the machines don't. They just follow the rules. So when all those rules need to be exact we really need to identify what rules are 'fair'. In fact, the root of this problem is that fundamentally there is no fairness in the world."

To illustrate the point, he offers the example of the driverless car confronted by two people running out in front of it at the last minute. "The car has no choice but to crash into one of them. Which one should it hit? The older? The younger? Richer? Poorer? ... Because humans can't make judgements in so short a time, we often say it's 'destiny'. However, the machine can analyse and make judgments at lightning speed, so there is no 'fate' and everything becomes a pre-defined 'decision'."