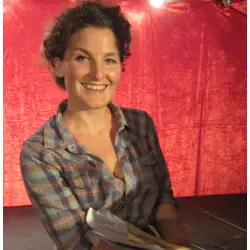

Alice Fraser

Alice FraserAlice Fraser is on tour with her new hour Mythos at MICF – a show that tries to unpack the stories and lies we tell ourselves and each other – ahead of runs in Perth and Sydney, when she speaks to us about the things that make her laugh, or, more to the point, what doesn’t.

“What makes me laugh?” Fraser ponders. “I can tell you what doesn't make me laugh probably better. Like cringe-y humour – I don't like prank shows, I always feel like they're too mean. Even things like The Office or Mr Bean I can't really watch, I can only watch with half an eye while I'm doing something else.”

She says she’s always been averse to what she describes as “cruel humour”, jokes that are pointedly at someone’s expense: “I think that’s something that’s been part of me from the beginning.

“Self-deprecating humour has never appealed to me because it feels like somebody bullying themself. And I don't particularly like it when people pick on audience members or make generalisations or stereotypes that are degrading – I don't enjoy that contempt from an act, either for themselves or for the audience.”

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

What does make Fraser laugh is “silly humour”, which she attributes to growing up on a diet of Monty Python, Marx Brothers movies and The Goon Show. “I like that kind of clever silliness.

"It also reflects how silly all of our kind of intellectual bullshit is."

“There's a pleasure and a delight of showing off something quite highbrow at the same time as really revelling in the silliness. I think both of them reflect on each other, that if you do silly-clever then you see how hard it is to do things that are silly. It becomes impressive – it makes the silly impressive. And then it also reflects how silly all of our kind of intellectual bullshit is.

“I remember the first Marx Brothers [film] I saw. The first movie my dad took us to was a screening of an old black and white Marx Brothers movie at the Village Cinemas in Randwick in Sydney, and I was there with my twin brother. And I remember being so impressed by the weird mirror routine that Harpo did with Chico, where they're sort of reflecting each other and pretending to be each other's reflections. I remember doing it with my brother, practising it and making our parents watch us do that sketch.”

She was “a baby then” who was “wildly impressed by the whole thing”. Now, she reflects on whether, watching a Marx Brothers movie as an adult, it would tickle her the same way. “I don't know if I would go back and watch it and find it as funny as I did. I think I would still find something that was impressively choreographed, incredibly precisely done, and also very, very silly, [and] I would find that very funny.”

Still, being drawn towards clever silliness doesn’t mean there aren’t things that Fraser laughs at almost in spite of herself. “I have a friend who always deliberately misses a high-five, and every time I fall for it, and it makes me laugh every time. He'll always offer a high-five and then when I go for it he'll deliberately miss by about a foot, and it's hysterical [laughs]. It's so silly but it's so much fun.”

The starting point for Mythos as a show was an argument Fraser had with a flat-earther online about the very existence of Australia – and by extension, Australians.

“He insisted that Australia wasn't real,” Fraser says. “And I thought well, y'know, it'll be very easy to prove that I exist and am real. And then I realised how hard it is to do, had a minor existential crisis of how difficult it is to prove that you're real to someone who insists that you're not.”

The idea that the Earth is flat is just one story people tell themselves about the realities of their lives and their world, and it’s relatively harmless, albeit stupid. Some such stories are much more destructive.

“From a more serious angle, we're living in a world now where there are so many different stories that people can choose to believe or not. One in 20 people in the UK say that they don't believe the Holocaust happened. And as somebody with Jewish heritage that's terribly shocking, and the only way I can deal with that is by thinking, 'They don't actually believe the Holocaust didn't happen, they just think that saying the Holocaust didn't happen is a cool thing to say, there's some sort of personality that they want to express by saying that.'

“We're living in this world where there's so many different stories that people can choose to believe – how do you work your way through that? How do you find a place of truth in all of that?”

Should comedians in 2019 by necessity grapple with difficult things, like the realities of a world beleaguered by rising right-wing extremism, climate change, fear? For Fraser, difficult things have always been part of her work, which has touched on painful subjects like the death of her mother from multiple sclerosis.

“I've always been fascinated by difficult things – I'm drawn to difficulty, I'm drawn to complexity, I'm always, always wanting to complicate things or make people question their assumptions.

“I do think comedy can do that maybe better than almost anything else because people are more open when they're laughing, they're not in an environment where they're trying to justify themselves or defend themselves or prove something about themselves. So you can actually talk to people and let them into a different view of the world.

"I think of all of the skills in the world right now, practising looking at things from another angle is one of the most important.”

“And even just showing them that there is a different view of the world makes them realise that how they see their world is also a view of the world, that there's more than one way to look at things, and then they get to practise that. I think of all of the skills in the world right now, practising looking at things from another angle is one of the most important.”

In fact, Fraser can point to the importance of joking in helping her to cope with those very same difficult things.

“My mum was sick when I was growing up – she had MS, which meant that at various times she would have accidents of all sorts in public, that would make her very upset, [and] that would make the people around very uncomfortable. And making a joke, relieving the tension, was incredibly important as a survival skill in those situations. Making everybody comfortable again was something that humour let me do.

“And then also, being bullied in high school – I went to an all girls school, so the bullying took the form of ostracisation, of being cold-shouldered or ignored. So if I could say something in class that would make people laugh despite themselves, that always felt like a victory.”

Alice Fraser is on tour now.