YOUNG & BEAUTIFUL

![]()

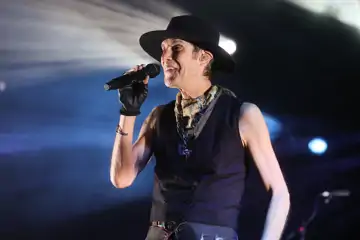

On the eve of her 17th birthday, on a family holiday on a postcard beach shot in saturated colour, Marine Vacth loses her virginity to a German ginge, removing it like some unwanted growth. Teenagers are famous for their out-of-control hormones, but the heroine of Young & Beautiful seems impossibly cold, unbearably practical. “It's done,” she says, dispassionately, to her pre-adolescent brother. “Don't tell mum.” It's a familiar first time experience - awful, rushed, in a public place - that snaps something in her; no sooner is Vacth back in Paris than she's online, taking up a covert, after-class career as a high-class call-girl. It's, to her mind, not so different to babysitting; although her bourgie parents, despite their progressive pretensions, may vehemently disagree.

François Ozon has long chronicled the barbarism and perversity of volatile youthful sexuality; especially through so many of his early shorts and his audacious 1999 provocation Criminal Lovers. The fact the film opens at the beach connects it to about half his filmography (1998's See The Sea, 2000's Under The Sand, 2004's 5x2, 2005's Time To Leave, 2009's Le Refuge); and there's a great scene where Vacth, when babysitting, rifles through the drawers of her employers, a direct call back to the spectre of the great Marina de Van in See The Sea. If those connections are somehow unclear” Young & Beautiful is Ozon regaining the cruelty of spirit that, long before cutesy costume dramas like 8 Women or Potiche, made him French cinema's enfant terrible.

Ozon is exactly the kind of filmmaker you want in command of this drama. The premise reeks of salaciousness and scandal, but he remains measured, quizzical, unafraid. He refuses to moralise on Vacth's choices or make her motivations explicit; to paint hobbyist prostitution as either of coming-of-age journey or self-destructive downward spiral. Her mother, Géraldine Pailhas, is invited to judge, harshly, when she discovers her baby-girl's secret, but her lacerating recriminations feel hollow, as if playing a protective part; whilst the momentary change-of-perspectives - from teenage transgression to parental revulsion - recalls Lynne Ramsay's maternal-nightmare We Need To Talk About Kevin.

Yet, Young & Beautiful never settles as mere provocation, instead becoming commentary on the hyper-capitalist, forever-online now; of youth and beauty as cultural currency, a natural resource to be exploited for profit. Aided by the internet's ease and capacity for anonymity, Vacth turns herself into a commodity, price listed like eBay; her self-worth conflated with her financial worth. That the digital grid encodes her teenage transgressions for eternity - that, when shit invariably hits the fan, her online actions and mobile-phone records are easily accessible - means this undoubtedly a 21st-century tale; making comparisons to nouvelle-vague classics like Belle du Jour and Vivre Sa Vie both misapplied and misguided.

But, it's not so much a portrait of sexwork circa 2013 than of adolescents eternal; Ozon filming real 17-year-old students reciting Rimbaud's nearly-150-year-old poem Romance to-camera in a striking, defiant device; then sitting them down to discuss the poem, and its themes. The thematic resonance isn't as profound as Abdellatif Kechiche's scripted discussions in Blue Is The Warmest Colour, but the themes linger. The footloose and fancy-free qualities of Rimbaud's romanticism stand in contrast to the self-serious Vacth; but, as she blithely dallies from john to john, equal parts precocious and clueless, the line “nothing's serious at seventeen” lingers. For her, this fucking-for-cash is an after-school lark, the very-real dangers holding no threat. Ozon places the audience in that space, though; situating viewers between obliviousness and threat, and leaving them to inhabit that unease.

"Wait, how many Tuesdays again?"

52 TUESDAYS

![]()

52 Tuesdays wears the formalist gimmick of its production in its title: once a week, every Tuesday for a whole year, the cast and crew would gather in Adelaide and film. It was documentarian Sophie Hyde's attempt to shake up the familiar production schedules of fiction films; to use that great emotional currency of the longform documentary - the passage of time, change written on the faces and bodies of the subjects - in narrative form. The narrative wasn't written with a regular script's tightness, too; instead, the actors were asked to inhabit situations, with the story, like a documentary, being fashioned through editing.

This approach - both in its table-setting backstory, and in the way it plays out on screen - is the best thing about 52 Tuesdays, a film that is sometimes as shaggy as that production back-story suggests. The drama is about a teenage girl (Tilda Cobham-Hervey) struggling through a highly-sexualised coming-of-age, whilst her mother (Del Herbert-Jane) simultaneously struggles with a to-male gender transition. In many ways, the film underplays its great of-the-moment dramatic premise, these ideas of gender and familial fluidity; whereas it overplays the drama of teenaged sexual scandal, and scatters in a few convenient soap-opera devices as it progresses. But, even when 52 Tuesdays deals in the familiar, its approach lends it an air of the unfamiliar; and Cobham-Hervey - a mixture of adolescent awkwardness and effortless transcendence - radiates star-in-the-making-light.