Inside Llewyn Davis

When a musician makes it - becoming sufficiently famous or cult-followed to befit biopic or rockumentary - their early trials, troubles, and tribulations become the stuff of legend. When they don't, they just become suffering. That's the unexpectedly-grim theme lurking beneath the seemingly-crowdpleasin' premise - those O Brothers recreate the Greenwich Village folk-scene in 1961, replete with Justin Timberlake in beard and sweater - of the latest film from the Coens. Inside Llewyn Davis displays Joel and Ethan Coen's meticulous approach to photography, set direction, idiosyncratic language, and self-reference, but also totals as an odd, tangental riff both more human and more hopeless than their familiar style-pieces.

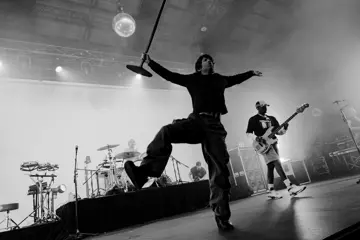

It's a movie about music-making leeched of its regular romanticism: the toil of the undergrounder's life unglamorous, unstable, and unenviable. Its titular character - played with a prickly, prick-ish attitude by Oscar Isaac - isn't a transcendent talent biding time 'til either fame or tragedy - or both - comes calling; instead he's the guy with the unpronounceable name best known, around the traps, for drunkenly heckling others. He's a staunch anti-careerist, clinging not just to his credibility, but to time-worn clichés of artistic suffering. He's an urbanised wandering minstrel, couch-hopping his way around the Eastside, never getting his shit together for fear it might taint his art. So he blows through the frigid streets, with a guitar under one arm, a box of remainders under the other (in a sublime-yet-sad gag, when crashing at the pad of Adam Driver's fellow struggling-troubadour, he looks to stash his unwanted LPs under the couch, only to discover it taken by a trove of Driver's own solo album). And, in the film's cutest gesture, with cat upon his shoulder.

This itinerate existence - an accidental anti-materialism - may preserve what little mystique he's mustered, but to those closest to him, called upon for loans of cash and places to crash, it makes him a loveable fuck-up no longer so loveable. “You are shit!” Carey Mulligan spits at him; her sweet, milquetoast-folkie stage presence - guys come to see her play, Max Casella's local promoter reasons, because they want to fuck her - a façade camouflaging a bottomless pit of seething hostility; most of it reserved for our guy. It's soon revealed Isaac may or may not have knocked her up; either way, he's paying for the abortion. So begins a black-comedy of coincidental errors: an anti-hero desperately out to scrape cash together, with results of varying disaster.

The Coens have a long history of daffy men caught in downward spirals, but this titular character doesn't have that same sense of victimisation; he's trapped by neither noir convention nor existential comeuppance. Instead, Isaac's failing folkie remains fervently committed to virtuous beliefs at odds with the world around him, refusing to compromise even when it borders on career suicide. Eventually, he hits the road on a cockeyed, Coenesque odyssey: hitching a lift with Garrett Hedlund's mute beat-poet and John Goodman's garrulous jazz musician (“we play all the notes,” he mocks, not just the same tired “cowboy chords”). The farther he gets from his stomping grounds, the more Isaac's lot seems dim; this whimsical trip towards fantasised salvation leading only to an impresario's dire appraisal of his careerist potential (“stay out of the sun”) and a headlong collision with reality; life less a lived-picaresque when you've holes in your shoes and nowhere to dry your socks.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

Inside Llewyn Davis is built on the comic, grotesque juxtapositions between its protagonist's quotidian humiliations and moments of musical transcendence. The pic stops still, several times over, to listen as Isaac wails traditionals with a conviction, a passion, a warmth, and a humanity absent from his off-stage demeanour. He refuses to play as a dinner-party parlour-trick, but will sing as an act of defiant trolling (in the car with Goodman) or to bridge the gap between wayward son and deathbed father. And he'll sing for his supper - for his very freedom - at a pass-the-hat folk club that feels far less like the stuff of nurturing, scene-making rock-mythology, far more a dive-bar drenched in drunkenness and failure.

In a perfectly-judged opening/closing device, the Coens repeat a performance of the same song - Hang Me, Oh Hang Me - so as to highlight how different it plays when, at first, free from context, as to how it feels after 100 minutes walked in Llewyn Davis's shoes. On close, he's 'earnt' the right to carol of suffering and woe, become the real deal. For a man who long ago bought the myth, it's a crystalline instant of artistic vindication, but it doesn't last long: no sooner has Isaac finally tapped into a moment of pure truth, than he's followed on stage by a young Bob Dylan. All his suffering is rendered meaningless, his career immediately reduced to a footnote in the formative days of someone soon-to-be vastly more successful. History is written by, and about, the winners; Inside Llewyn Davis is the Coens' valentine to its noble losers.

No, we do not want to hug you, Mr. Hanks.

SAVING MR. BANKS

![]()

When John Lee Hancock's Magical Negro monstrosity The Blind Side traipsed through the 2010 awards season, it clearly gave him a taste for it: Saving Mr. Banks, his follow-up, is a most fragrant piece of desperate Oscar-bait. A winsome valentine to get-up-and-go Old Hollywood, it's a based-on-a-true-story tale (yes: the real photos of the real people are in the credits) that conflates film-biz history with actual History; the troubled early-adaptation of a twee musical judged worthy of fastidious recreation. Brought to you by Disney, it's pure Branded Entertainment: filled with a walk down Main Street U.S.A., a Mickey at every turn, and nearly as much repurposed Mary Poppins footage as there was The Shining in Room 237.

Its premise'll make an aging Academy member instantly tumescent: Walt Disney (Tom Hanks!) must convince P.L. Travers (Emma Thompson) to sign over Mary Poppins' screen rights; the drama's Studio Executive a visionary hero, its Writer a petulant egotist absent any business savvy. Its vision of Los Angeles a half-century ago isn't just a chance to recycle leftover Pan-Am sets, but a comfortable, nostalgic, thank-God-that's-ancient-history reminiscence of the last horrifying time a writer actually had any power.

Kelly Marcel and Sue Smith's screenplay juxtaposes dual narratives: Thompson landing in Los Angeles to go over proposed scripts, whilst remembering her Outback childhood 50 years prior. “It's as if my subconscious is after me,” she laments, explaining away the device where every pear or carousel or gaze out a window leads to yet another dissolve, another trip back to a chronologically-staged past building towards a great dramatic reveal; to the source of all the bitter writer's endless pain. Turns out Travers has Daddy Issues: Colin Farrell gambolling about as dadydreamin' drunken-Irish Da, who keeps clean-shaven for frisky lil'-Miss kisses and takes her horse-ridin' on his lap (shown in slow-motion, it resembles naught but a sex scene, hopefully intentionally). Luckily, in the narrative now, Disney's on hand to serve not just as corporate brand-builder, but mystical therapist, able to grant tortured artists their salvation with each adaptation.

On a thematic level, Saving Mr. Banks is worthy of weary eye-rolls. But goddamn it if Thompson isn't genuinely great! Playing Travers as derisive, disapproving school-marm, she's clearly having a ball; and when she spits that she's “positively sickened” by the thought of suffering a morning at Disneyland, it's a tonic for the flick's more saccharine notes. The cast, in general, is way game: a slumming Paul Giamatti gives his minor-role grace; Jason Schwartzman is all mighty eyebrows and blinding white teeth, like a Sylvain Chomet cartoon brought to life; Rachel Griffiths blows through with a seminal air of simultaneous cruelty and whimsy; and Hanks finds life, contrast, and conflict in what could've been a piece of sketch-comedy mimicry. Which means that Hancock's portrait of Disney feels pretty Disney: it's so pleasingly-played and slickly-delivered that its more sickly tendencies are sugared away.