“All the Saints were rebels,” says Father Bob Maguire, admiringly, mid-In Bob We Trust, Lynn-Marie Milburn's excellent documentary portrait of the renegade 'people's priest' and unlikely media personality. It could've just as easily be called The Passion Of The Bob, with Maguire, edging towards 75, both passionate orator and outspoken advocate of the priest-as-social-worker; an irrepressible source of energy, still rising at the crack of dawn to open up the doors of his South Melbourne parish. Or, it could've been called The Gospel According To Bob, the loquacious larrikin setting the tenor of the edit with his rapidfire verbiage. The film begins in a breathless rush, a montage of stock biblical imagery - from Hollywood epics and B-movies, devotional artworks and dark woodcuts - cut up to match the cut-up's freewheelin' evocations of the history of the Catholic church; and, through that, effectively, the history of the world.

For a man of the cloth, Maguire is pleasingly irreverent when talking about Christianity's path through the ages. He portrays it as a political movement that was quickly coopted by the-powers-that-be: the Catholic church on hand to bureaucratise and corporatise what was once a rebellion, consolidating power and wealth in the hands of a select few. The film's central drama is a struggle between those powers-that-be and the priest himself: the Church keen to usher the beloved Father towards retirement, so as to silence his dissident voice, and to seize control of the considerable wealth in his diocese. Maguire never has a crisis-of-faith, just a crisis-of-conscience; his every day spent working within a hierarchy that, to him, is a system of oppression. “There's gotta be a better religion somewhere,” Maguire laments, seeing the Russian Orthodox branch's demonisation of the “cheeky girls” of Pussy Riot as being a sign of an institution that's lost its way, and, worse, its sense-of-humour.

In Bob We Trust, thus, chronicles a subject caught between his beliefs - in the teachings of Christ; in the simple edicts of helping those less fortunate and speaking out against injustice - and his “company man” devotion. It's an profound portrait of what it means to have faith in the 21st century, but it's also an allegory for millions of non-denominational workers in a multinational world. Just as Maguire helps the poor under the banner of an institution that shelters paedophiles and indirectly propagates the spread of AIDS, so do so many otherwise-upstanding people work for News Corp, Goldman Sachs, Siemens, Pfizer, Dow, Monsanto, et al. There's no greater aid to evil, Maguire offers, than when good people do nothing, and he's committed to doing something. Father Bob's moral conflict is whether to try and transform the church he's given his life in service to, or whether to go it alone, like so many rebels before him.

Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer isn't a great piece of documentary filmmaking; but, in some ways, it doesn't need to be. All Mike Lerner and Maxim Pozdorovkin need to do is point their cameras at the titular Russian performance-artists, who - speaking behind a glass shield in court; the treasonous prisoners in a televised spectacle eerily reminiscent of the Stalinist show-trials of the late-1930s - are eloquent, thoughtful, and unwavering in their conviction that Putin's Russia is a corrupt and oppressive regime. The three members of the Moscow-based “oppositional activists” were famously arrested in February of 2012 for performing a 'punk prayer', provocatively titled Mother Of God Drive Putin Away, inside Christ The Saviour Cathedral. Lerner and Pozdorovkin seek to add depth to a story that generated endless headlines and infinite tedious opinion-pieces, yet was often rendered without any complexity. And, most of all, they seek to turn these demonised women - Nadia Tolokonnikova, Katya Samutsevich, and Masha Alyokhina - into human beings.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

Barbara Kopple's mediocre 2006 documentary Dixie Chicks: Shut Up And Sing tried, unsuccessfully, to turn those accidental-rebels band into righteous dissidents. Rather than coming off as rebels with a cause, the Dixie Chicks were grist in the great media-machine, a figure-of-debate who weren't actually out to rustle feathers; that movie's 'drama' watching a corporate country band try and minimise the cross-promotional damage with their sponsors. Given how swiftly Pussy Riot became indie music's great cause célèbre, it's easy to be suspicious that these Le Tigre-loving lasses had been turned into iconic figures out of convenience, as yet another unseemly chapter in the media's ongoing white-women-syndrome (the injustice of Tolokonnikova's imprisonment infinitely amplified by the fact that she's incredibly beautiful). Yet, the moment they open their mouths, Tolokonnikova, Samutsevich, and Alyokhina show themselves to be the real deal; the definitive article; the righteous dissidents that the media dreamed. Even if A Punk Prayer only gets to speak briefly to its key subjects, it, most importantly, gets to show them having their day in court. And, in the face of their imminent sentencing, each delivers a final statement that stands as poetic, defiant rebukes of Russia, its leaders, its media, its court, their own trial, and the very notion of 'justice' in a totalitarian regime.

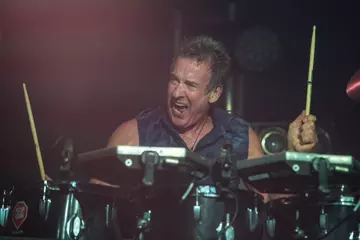

Metallica: Through The Never is a far more problematic - and far more unintentionally-hilarious - portrait of the cultural cachet of the rockband. It's an inevitable piece of merchandise from the self-proclaimed World's Biggest Band: a 3D concert spectacular of the aging, leather-clad men of metal playing all their hits (note: almost entirely pre-1991), intercut with music-video 'narrative' interludes in which Dane DeHaan plays a road-crew gopher sent out into a mission into a post-apocalyptic night rife with Molotov-cocktail chic, warzone motifs, and fancy-yet-nonsensical imagery.

As Metallica hit a stage forever festooned with fireballs, ridiculous props (Electric chairs descending from the ceiling! Tesla coils riding the lighting! The And Justice For All... statue assembled by a roadcrew on stage! A stage-hand catching on fire!), and elaborate video gimmicks, outside, in the narrative world, DeHaan tries to escape a gasmask-wearing vigilante on horseback, amidst streets in which Anonymous-esque gangs of rebels and riot-gear-clad cops stage a Royal Rumble. It's faceless masses vs faceless masses, and “'visionary'” director Nimród Antal (the guy who made Predators, and for whom that descriptive cannot have enough scare-quotes around it) makes sure that the carnage is politically neutral; Metallica, like Michael Jordan, avoiding making a political stand so as not to alienate any potential consumers.

Sadly - or, if you're into mocking shitty movies, awesomely - Through The Never isn't just noncommittal on the political, but the rational. Leaving behind the more head-scratching elements of the concert itself (chiefly: the weird irony of a crowd chanting “Obey your master!”; why a coffin would shoot fireballs; how Robert Trujillo's hair remains permanently wet), the inexplicable adventures of DeHaan's minimum-wager are beyond baffling. The character is, in a piece of sledgehammer-subtle foreshadowing, named Trip; and, so, into a surreal nightmare he descends. And, sure, in this world of galloping riffs and swooping-crane-shots-homing-in-on-Lars-Ulrich's-bald-spot, shit doesn't necessarily need to make sense. But when DeHaan douses himself in petrol and sparks a lighter before engaging in climactic fisticuffs with a gang of marauding interlopers, he's not just setting himself on fire, but logic itself.

The Italian Film Festival is currently taking over cinemas, and it's headlined by The Great Beauty, the latest film from Paolo Sorrentino; who, along with Matteo Garrone, has been a key figure in re-establishing Italian cinematic culture on a global level. Returning to Italy after making his oddball English-language debut, This Must Be The Place, in America, Sorrentino once again stages a visual marvel. The Great Beauty sprawls out to two-and-a-half hours of old-grandeur spectacle and winking Fellini homage, both paying tribute to the Holy City whilst condemning modern Italy as a country in decline, besotted with its glittering history.

A character herein has “the keys to Rome's most beautiful buildings”, and Sorrentino's film happily tours through Roman ruins, clandestine crypts, and hidden-away galleries; in thrall to secret nocturnal words, and the lavish parties of a decadent high-society steeped in wealth, gossip, and decay. Its central character is a misanthropist writer who hasn't written anything in decades; his whole life lived as “king of the socialites”. Sorrentino's recurring collaborateur Toni Servillo plays him as aging, empty, lonely playboy presiding over a neverending string of ridiculous parties, that're played out on the empty summer streets that serve as Rome's eternal stage.

Even at his best (and The Consequences Of Love, The Family Friend, and Il Divo was quite a run), Sorrentino's relationship to plotting has been non-committal; the filmmaker part abstract auteur, part videoclip director. The Great Beauty is far-and-away his least narrative feature: the Sorrentino more interested in staging grand visual gambits, camera always moving, and peering at the faces and bodies of his cast of oddballs; gazing on a tattoo of a dismayed Pope John Paul II or the shrivelled face of a toothless 104-year-old Saint with tender reverence. There's a phrase, herein, where Servillo describes himself as being “driven by simple curiosity in other people”, and it's as if he's speaking Sorrentino's filmmaking oeuvre out loud. The film's final shot - running, gloriously, under the closing credits - floats down the Tiber during magic hour; the focus, assumedly, on the architecture of the film's metropolitan muse. And yet, Sorrentino keeps peering up at the faces of passersby on the bridges above, his curiosity always alighting on individual idiosyncrasy. He may not be a 'humanist' in the traditional cinematic definition, but even his portrait of a misanthropist comes with loving humanity; the 'grande bellezza' here not Rome, that faded dame, but all the people that pass through it.

![LT [Leanne Tennant]](https://media.themusic.com.au/images/standard/Artists/L/leanne-tennant/2601-lt-she-is-aphrodite.360x240.webp)