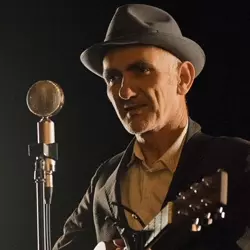

Paul Kelly

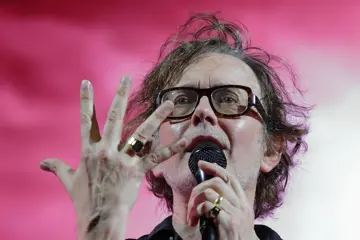

Paul KellyIn honour of the 100-year celebrations of the Irish Republic, Culture Ireland recruited Camille O'Sullivan - the chanteuse who's found fame for her dark cabaret takes on Nick Cave, Jacques Brel and Radiohead - and Paul Kelly, the wry Melburnian storyteller and Australian icon - to collaborate for the Dublin festival. "We met at Paul's house, he made us lunch; it was very surreal, being made lunch by Paul Kelly," recounts O'Sullivan. "We just said 'What's your favourite Irish poem? What's your favourite Irish literature?'"

The result is Ancient Rain, in which O'Sullivan, Kelly and Feargal Murray set Irish verse to song. There's poems by WB Yeats — "[His work] may be 100 years old, but Yeats is very alive and well to the people of Ireland" - Eavan Boland, Seamus Heaney, Paul Meehan and Patrick Kavanagh, and even an acted-out passage from Joyce. After premiering in Dublin, Ancient Rain will arrive for a run at the Melbourne Festival.

"It was very surreal, being made lunch by Paul Kelly."

"Poems hold a mirror up to yourself, both personally and as a people," says O'Sullivan. "[This is] a collection of poems that have great melancholy, dark Irish themes: love, death, mother, father, lover, loss, return. Most Irish poems are bleak, you can't ignore it. But, I'm a great lover of Nick Cave's music, and that can be quite bleak too. Like any good theatre it's thought-provoking stuff."

O'Sullivan and Kelly have both set poems to music before: O'Sullivan turning Shakespeare's The Rape Of Lucrece into a full theatre show of songs; Kelly adapting Shakespeare, too, for Seven Sonnets & A Song, and Yeats, Tennyson, Dickinson, Slessor and others for Conversations With Ghosts. Yet despite their experience, collaborating didn't come easily as the pair had to reconcile their distinctly different approaches.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

"I'm quite an intense person emotionally, so I like things to be cool, then [when] it explodes there's a real moment of surprise," O'Sullivan offers. "Paul likes it to be as straightforward as possible: this is the lyric, this is how it is. I like things to change as they go, he likes a direct, clear route. He would laugh sometimes at my passionate, dramatic, emotional reactions... It became very clear that we were two very different kind of people, but we both have a love of the lyric, and of telling stories through song. I was brought up on Kurt Weill and Jacques Brel, he's more Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen, but it's very similar: long, seven-minute, narrative storytelling. But our voices work well [together], and we knew something good would come out of the two of us teaching each other how we'd approach things."

The poems, O'Sullivan thinks, inevitably had the final say: the words suggesting melodies, pace, delivery, adding music a process of building on the feelings already there. "You can multiply the emotion by setting a poem to music," she says, "and sometimes you can soften the starkness of words, make bleak poems no longer seem so bleak. They can be sad, but with a sense of hope."