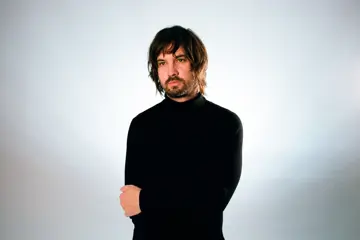

Chris Madak is an interesting musician. Over the past five years, he's delivered a steady stream of harsh, confronting works constructed through invented electronic instruments and old-school samplers – almost exclusively to mediums like vinyl and cassette. More intriguingly, he's consistently done so with a precision and academic rigour more suggestive of an almost scientific outlook than any inherently musical perspective.

“Yes, I think my engagement with sound has always been basically intellectual and generally about decoding things,” Madak reflects. “If I had to chalk that up to something, it might be that I come from a family of classically trained musicians who listened to virtually nothing else around the house. So, my initial habituation was to the sort of music in which the real action lies in puzzling out how all the moving parts fit together, so to speak.”

There's a thread of contradiction that runs through Madak's work as Bee Mask. It's raw, almost spiritual work of seemingly pure expression – which nevertheless appears to be the product of a frighteningly sophisticated intellect. The Cleveland musician's relationship with fidelity is perhaps most emblematic of his kinks. Defined through meticulous post-production, Bee Mask records are often released through lo-fi mediums like cassettes.

“The idea of fidelity is deeply fascinating and deeply problematic for studio music,” Madak explains – emphasising that his music is not so much recorded but constructed. “Sure, we can talk about the linearity of a playback system within certain parameters but if there is no primary acoustic event, what is even there to which the information on a record might be more or less faithful?

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

“Even if there is an original event, I think it's always useful to ask ourselves what we're actually hearing when we think we're hearing 'fidelity', because the things that we listen for are culturally specific and can change to hilarious effect with time and circumstances,” the artist elaborates. “Where cassettes are concerned, if the work was produced specifically for cassette, then how is the sound of the cassette not part of the sound of the work?”

The limits of Madak's clinical perspective highlight that contradiction. While Madak may view and construct his work within highly intellectual frameworks – to the point where actually playing his material live is physically impossible (he resorts to a mixture direct playback and improvisation) – he seems reluctant to reduce his work to a solely intellectual exercise. He can't speak to his specific mission statement for Bee Mask, for example.

“I've had a handful of different ideas about this over time, but for now I'm mostly motivated by the sense that I'm following the thread of the work I've already done rather than seeking an external rationale for what I'm up to,” he muses. “It's important to think deeply about why one does what one does and to have a 'research and development' aspect to one's practice, but it's just as crucial that the work be able to stand on its own two feet.

“I think about the future to a fault,” the artist reflects. “There is definitely some sort of horizon to Bee Mask, but I'm hesitant to commit myself by saying exactly what I think it is at this point. As I've said in the past, I think the important thing is for me to retain a sense that the project is mine to do or not do anything with at any given time. Right now I have some plans for the future that do involve Bee Mask.

“Once I've taken care of them, I'll know whether or not I have some more.”