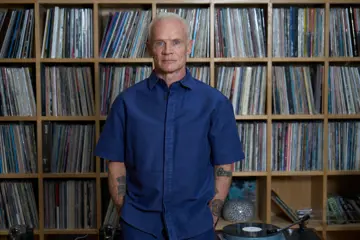

Augie March

Augie MarchFor the last five years, it’s seemed to all and sundry that Victorian outfit Augie March were no longer a going concern. Not only had frontman and creative engine room Glenn Richards released a solo album (2010’s Glimjack) — never a good sign as far as the viability of a band is concerned — but he’d also decamped to Tasmania to escape the hustle and bustle of Melbourne, so for all intents and purposes Augie March seemed done and dusted.

Fortunately, appearances can be deceptive. For the last couple of years, the members of Augie March — Richards (vocals/rhythm guitar) plus Adam Donovan (lead guitar), Edmondo Ammendola (bass), David Williams (drums) and Kieran Box (keys) — have been reconnecting at Richards’ Tasmanian studio (or transcending the tyranny of distance via the wonders of technology), not so much in secret, just in a manner which could be described as more private than public. They’ve been busily working on what would become the band’s newly-minted fifth album, Havens Dumb, which dropped fully-formed from the virtual darkness and represents a fine return to form for the quintet.

But let’s step back a little. Having formed in 1996, Augie March’s career spent its nascent years on a steady upwards trajectory. Their first couple of albums — 2000’s Sunset Studies and 2002’s Strange Bird — gained plenty of critical traction and built their public profile significantly, but it was in 2006 that all of their labour finally coalesced with the release of their third album, Moo, You Bloody Choir, and its breakout single One Crowded Hour. Suddenly, they were doyens of the Australian scene; they were nominated for six ARIAs, won triple J’s Hottest 100, took home the highly prestigious Australian Music Prize, the album went platinum in Australia and started gaining traction in the States… everything was coming up Augie.

Yet somehow, when it seemed they had the music world at their feet, the wheels fell off, and fell off quickly. There was pressure (external and internal) to match all of this success on the follow-up, but sessions for what would become the presciently-titled Watch Me Disappear (2008) did not go smoothly, either in terms of their relationship with producer Joe Chiccarelli or within the band’s own ranks. The resultant album didn’t gel, nor did it really register with fans, so all of that hard-earned momentum was lost — by the end of 2009, Augie March had entirely ground to a halt. Until now.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

“I moved over here from Melbourne about three years ago, and while I had other projects going I pretty much started from day one on this one when I got over here, so some of the tracks that ended up on the record where among the first that I was writing,” explains Richards of Havens Dumb’s beginnings. “So I guess it’s been a three-year stretch for me, and most of the work that the other guys did was late-last year and early-this year.

"If it wasn’t working, we simply wouldn’t release it, so it had to be at least a satisfying record from our perspective."

“With some of those earlier tracks, it’s easy for me to look at them now and think that one or two of them are definitely just experiments to get me back into the rhythm in a new environment, but then there were a couple of others that were basically template Augie tracks. I think I probably knew that I was starting to rebuild the empire back then.”

Because of these ad hoc beginnings, the band didn’t have much of a chance to really map out what they wanted Havens Dumb to sound like or represent, essentially letting the songs dictate the overall direction.

“From a musical standpoint [we probably let songs dictate the direction], but whether it was overtly spoken about or not there was certainly a shared expectation that we wouldn’t compromise on this one — if it wasn’t working, we simply wouldn’t release it, so it had to be at least a satisfying record from our perspective,” Richards contemplates. “We wanted some quality control if we were going to introduce ourselves again and not let anybody down this time.

“I haven’t really listened to it much since it’s been finished. Because I did a lot of it down here in Hobart on my own, it’s still quite difficult for me to separate the experience of making it from the result. I haven’t been able to have a proper, neutral sort of listen yet. But I haven’t had any feelings of disappointment on this one, and that’s a good sign.”

At some point, however, the Augie March members did think about staying true to the band’s substantial legacy.

“When it got down to the last couple of months, when we were deciding what tracks to leave out and that sort of thing — even how long the record was going to be — there’s always been a bit of an argument with us about whether we should make a succinct ten-track album for a change instead of these great, long, sprawling things,” Richards smiles. “I always listen to those points, but the way I hear [the album], it is a great, long, sprawling sort of ambitious thing, and it does have a few stories to tell, so in my mind the legacy we have is probably making quite difficult records at times but rewarding ones that live with people for quite a while. I wanted to make another one like that and I think we kind of did.”

While Richards doesn’t tend to view Augie March as a commercially ambitious beast in the truest sense of the term — even during that fertile first tenure — he concedes that they did eventually compromise their collective vision to assuage business-related concerns, which was ultimately one of the contributing factors to their initial downfall.

“I guess we arrived around the time that a lot of indie bands were starting to have success — you had your Spiderbaits and Custards, and probably Frente was a big one back then — but they were starting to get a lot of attention from radio and major labels and that sort of thing,” he reflects. “We signed to an independent label that was in the process of being bought up by a major, so we kind of got swept up in that, but there was still very much a focus for most bands we knew — and most Australian bands in general — on just trying to make something as unique as possible and as ‘yours’ as possible. I don’t know if that approach is naïve now, but speaking for myself it’s incredibly difficult to make a living — I don’t see myself as that far removed from someone trying to scrape a living from being a visual artist or writing a novel; it’s never going to be a big pay day unless you strike it lucky. That’s kind of the best way to do it and still be able to live with yourself, and that’s not ever going to change. When we did listen to various voices saying, ‘You’ve got to tidy up your production,’ and, ‘Cut a verse here and a verse there and get to the chorus quicker,’ it ended up destroying the album and destroying the feeling that we had about making music for a while. It’s not a path that I think we should ever take.”

This is hardly a novel tale — in musical terms, acquiescing to external pressures regarding one’s artistic vision never tends to end well.

“It does happen and it sounds like a cliché,” Richards admits, “and obviously they’ve got interests at stake, but if you’re too exhausted mentally and probably physically like we were to put up much resistance to that, then you find yourself in trouble pretty quickly and that summarises pretty simply what happened to us towards the end. We needed to have a break before we made another record, and we made the mistake of just going straight into it.”

Richards further attests that the band felt a hefty burden of expectation following the comparatively runaway success of both Moo, You Bloody Choir and One Crowded Hour.

“I think we were willfully oblivious to it at the time because we just wanted to keep sane and not believe a hell of a lot of the nonsense — because it is nonsense. Something you do maybe strikes a note with some people and it goes okay, but then we ended up being on a label that we’d had no interest in signing to but we ended up there because of the machinations of corporate business, and their expectations (or their hopes) were that we were going to be the next crossover act and they’d have another Coldplay or whatever on their hands. But obviously we weren’t pretty enough or shit enough to be that band,” he laughs. “Despite their best efforts to make us that band. So there were expectations and I guess we let those expectations down.”

Now they’re back, free from any such shackles, and seem to be chomping at the bit artistically. Havens Dumb is a wonderful-sounding collection — was Richards having his own studio set-up a factor in achieving these lush production values?

“That’s at the heart of it,” he concurs. “If you’ve got any sort of clue as far as the engineering side of things go — even the most basic skills — time is your greatest asset. I probably could have spent a bit more time on a few things, but I would have gone insane if I did. We essentially had drums and bass from a couple of different studios and set-ups, and it was just a matter of marrying tones and trying to get everything sounding like it was all in the same room. We did nothing terribly differently from what we’d done before in terms of playing live in a room — we did that, but then we only kept the drums and bass and then most of the overdubs I did here. So it was just a process of getting a tone up for a guitar part, and it would sound great to your ears and then you’d hear it recorded, and it simply doesn’t match the feeling of the other instruments, so having another week maybe to spend on that is a great feeling.

“I think we kinda got there — it all sounds like it hangs together pretty well. A lot of it’s demos as well — a few of the tracks are really just stuff I did a couple of years ago, thinking, ‘This one’s worth putting a bit of effort into,’ and then the other guys liked it and we decided we’d just track drums and bass to the demo and leave it as it was. It’s kind of difficult to determine which ones those are — not difficult for me, obviously — but it sort of sounds quite natural, so I’m really glad about that. That’s testament to the other guys just knowing so intimately what’s required of the songs that I write — I don’t think you lose that. It doesn’t matter whether you’re playing live together a lot or not, it’s just a second-nature thing.”

Is there a lyrical theme tying the Havens Dumb tracks together, whether penned consciously at the time or becoming clear in hindsight?

"If anything, thematically, it’s all about pointing the finger at myself and trying to explore the reasons why I’m not being a better version of myself."

“To an extent,” Richards ponders. “I came over here not just because I was finding it difficult to survive in Melbourne and looking for a place where I can record — it was going to be ridiculously expensive to set anything up in Melbourne — but I also just wanted to get out of there because I was finding that the way I was going about things, not just the songwriting but largely that, wasn’t cutting it. I was out of the good habits and into the bad habits — basically finding too many distractions — in Melbourne, so to an extent the last three years has just been a process of trying to work myself out a bit, and trying to get healthy in different respects and get back to approaching songwriting with a healthy attitude. Which means that I don’t leave shit unfinished and think that that’s good enough — all of those terrible habits that it’s easy to slide into when you stop respecting the process and start thinking of your craft as nothing more than a hobby. And I think I was starting to develop a pretty unhealthy disrespect for the entire process.

“So if anything, thematically, it’s all about pointing the finger at myself and trying to explore the reasons why I’m not being a better version of myself. And from there, I guess because I wanted to avoid writing a diary for people — because that’s pretty boring when people do that with their songs — I looked towards what was going on in Australia as well, culturally and politically. And I saw a bit of mirroring going on there, I was starting to lose myself a bit — in many ways I think that Australia is unnecessarily going down some pretty crowded paths — so there’s a little bit of that in there as well. There’s a little bit of the micro and the macro going on, although it’s pretty hard to pick that up. It’s also just a collection of songs which feel like they should go together — that’s pretty much how all of the Augie albums are: songs that feel like they talk to each other even though they might be living in different suburbs.”

"I was possibly drinking a lot at the time when I first got over here and I think I just let the anger and the imagination go to work.”

The somewhat unsettling album track Definitive History is a good example of lyrically looking at the bigger picture, dissecting Australian culture in broad strokes in relation to one specific incident.

“That one is one of the really early ones — one of the demos I was talking about — and, at the start, I wasn’t thinking that it would be an Augie track by any stretch,” Richards tells. “I think when I first got [to Tasmania], someone was telling me about an incident that happened just down the road from where I was living — the last verse is about this poor young exchange student who was picked up by these two guys and basically murdered, and not before certain awful other things were done to her. And I know that happens quite a lot, unfortunately, but it just seemed extremely random to me and sort of exceptionally awful — if it’s possible to grade these things. I guess because it happened around the corner and in such a quiet town it started me thinking about how we still value a certain ‘ockerness’ in Australia that’s perhaps not as innocent as it used to be. That knockabout attitude which, to my mind — having grown up in country Victoria and witnessed the dark side of it — is a little bit aggressive, and sort of unnecessarily so. The rest of the song basically came out of that, how we tend to value certain character traits which, at the very least, are not explored very well in our cultural imaginations. They’re limited and often at root quite possibly evil. I was possibly drinking a lot at the time when I first got over here and I think I just let the anger and the imagination go to work.”

With his band back together and a new album on the shelves, Richards is now looking forward to reconnecting Augie March with its excited followers all over the country in the live realm.

“Obviously, with me being over here, it’s a little more difficult for us to get together that often to rehearse, but I’m already booking flights months ahead and organising stuff like that, so I’m kind of hoping that the distance is going to make the times when we get together all the more intense, and we’ll be more than ready to play these songs,” he says excitedly. “I think that some of these new ones will be quite mighty onstage — I hope that we can replicate them a little better than last time when we were playing towards the end. That was another thing that we got a bit lazy about — replacing sounds with something that will ‘just do’ — whereas hopefully this time around I think we’ll make a better go of making them sound as good as they do on the record. That’s the power of the live performance, and I’m really looking forward to getting back out there and amongst it.”