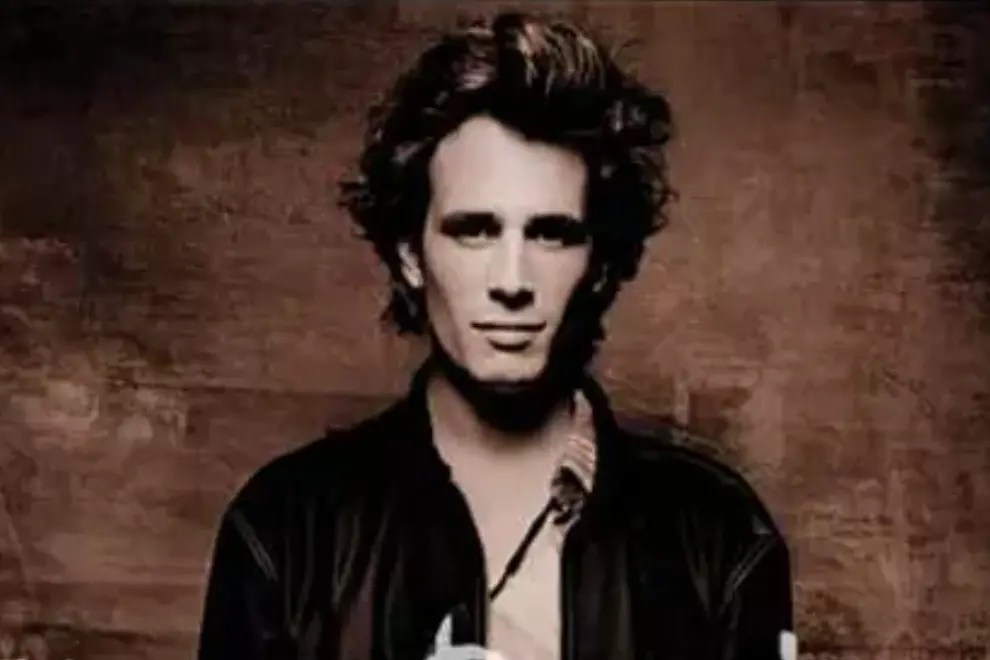

Jeff Buckley

Jeff Buckley“I’ve got something I’d like to play you,” the woman from the overseas label announced.

It’s the start of 1994, and I’m at a Sony sales conference on the Gold Coast. We’ve been running through the major priorities for the year – Celine Dion, Mariah Carey, Pearl Jam and C+C Music Factory – when the representative from the company’s New York office mentions a new signing.

“I’ll play it during morning tea,” she says.

As she pressed play on the CD, you could hear a Mojo Pin drop. The Sony staff – music fans, grizzled music veterans and cynical indie types – were all united. No one had to say a word. The look on everyone’s face said it all: “This guy is special.”

In that moment, Jeff Buckley became a superstar in Australia.

Hearing him sing Hallelujah for the first time was a revelation. Nothing needed to be said. It was as if Sony’s Australian staff made a pact: we’re going to make this record a hit.

Jeff Buckley’s debut album, Grace, was released in the US 30 years ago today. The album’s Australian release came the following month, when Inpress editor Andrew Watt put Buckley on the cover and eloquently explained the album’s appeal. “Every now and then a new artist comes along whose sheer quality and artistic vision is so obvious that you just know you’re going to be listening to him for a long, long time.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

“Grace is an album that seems so complete and so vivid in its expression that it’s almost an insult to try and deconstruct it and examine it to try and find out what makes it work.

“Probably the highest compliment that can be paid to Grace is that it’s timeless. It’s a brilliant album now, it would have been 10 years ago, and it will be in 10 years’ time.”

The record company bio that accompanied Grace had a section where the label listed what format it fitted. Grace ticked most of the boxes – alternative, AOR, easy listening, heavy metal, jazz, jazz/rock and “all other”. But Buckley responded: “That’s all just useless typing … everything it’s not, it is.

“What is it?” he added. “It’s just American music.”

And yet, Grace didn’t connect with American audiences. It peaked at number 149 in the US. Australia was the only country where it landed in the Top 10.

The American critics were initially unsure of what to make of the album. “Jeff Buckley sounds like a man who doesn’t yet know what he wants to be,” stated the three-star review in Rolling Stone.

John Encarnacao had no such reservations in his four-and-a-half-star review in Juice. “What kind of person wouldn’t like this disc?” he asked. “Maybe someone afraid of involvement. Or someone unprepared for music to penetrate their outer layers. Or anyone who rolls their eyes at the names Joni Mitchell, Neil Young or Sinead O’Connor. Grace is one of those sacred recordings.”

Grace received some play on US college radio but was shunned by the mainstream stations. “The songs were too long, and they didn’t have any hooks,” Buckley explained, relaying the complaints of the American radio programmers.

“It’s all a question of taste. I have no idea. I don’t know how their minds work, and if I ever do find out, I’ll hang myself from the nearest tree. I’m not really bitter about it at all.

“It’s a total crapshoot dealing with radio, so it doesn’t matter. Just so long as people come to the shows and enjoy it and get what they want, I can’t ask for more.”

And that’s exactly what Australians did – they embraced Buckley live. That first Jeff Buckley tour in 1995 is referred to in the same hushed, reverential tones as The Beatles’ 1964 visit and Nirvana’s shows in 1992.

You had to be there.

In Melbourne, Buckley did three shows at small venues – the Lounge, the Prince Patrick Hotel and the Athenaeum Theatre, as well as a set live to air on Triple R’s rooftop.

“His shows caused the biggest buzz in town since the Stones were here in March,” I wrote in Inpress.

I took my friend Nova Weetman to the Athenaeum show. She wrote about it in her recent book, Love, Death & Other Scenes. “I was down the front,” she recalled, “weeping as the strains of Hallelujah lifted us up.”

Buckley was a potent mix of Jackson Browne and Jimmy Page. He had the heart of a poet. And he could rock like a god. As one Rolling Stone live review said, “The punchline is, Jeff Buckley can get away with anything.”

Interviewing Buckley was no easy task. He seemed troubled, knowing that the interviewer would inevitably ask about his father.

Jeff’s mother, Mary, had been briefly married to a then-unknown Tim Buckley. When he was eight, Jeff spent a week with his dad; apart from that, he never knew him. Two months after that meeting, Tim Buckley died of a heroin overdose.

The young Buckley loved record stores. “They’re a really emotional place,” he said. “All my life, I tried to work in one, but they never accepted me, and now I’m in them. I go to Tower Records and see all these lives in the bins.”

He noted the sad irony of his record being filed next to his father’s catalogue. “Separated all our lives, and now I’m right there in the bin next to him.”

David Browne, the author of Dream Brother, the biography of Jeff and Tim Buckley, noted that the younger Buckley “was painfully aware of the mistakes Tim had made in his life, and struggled to avoid them”, though “the weight of acclaim helped undo them both”.

That first Australian tour sent Grace into the Top 10. I remember a backstage scene when a Sony rep informed Buckley that the album had gone gold and was headed for platinum. “But do I really want that?” the artist responded.

In Sydney, he visited Bondi Beach at sunrise. “I tried to swim, but the water was too cold,” he smiled. “My nuts totally contracted into my body.”

Thirty years after it was released, Grace has gone eight-times platinum in Australia, and it remains a consistent seller.

Buckley returned in February 1996 for bigger shows, forging a rare connection with Australian audiences.

On the morning show on ABC radio in Melbourne, Raf Epstein has a popular segment called Changing Tracks, where a listener talks about a song that was playing at a pivotal moment in their life.

Recently, Julie recounted her memories of driving down Puckle Street in Moonee Ponds in September 1995. “I was listening to triple j,” she wrote. “I had just given birth to my only daughter … and I was in a loveless marriage. I was feeling extremely emotional and desperate. My husband had not wanted to be a father and was reluctant to involve himself in parenting.”

Like Tim Buckley decades before, Julie’s husband said, “I don’t want this.”

She realised she would be better off on her own.

“Listening to the radio that morning, I heard Jeff Buckley for the first time,” Julie continued. “Singing with a lilting, powerful, emotionally charged voice, he seemed to soothe my pain, and it lifted me out of the hole I had found myself in. I bought the CD that day, and his music supported me through probably the worst 12 months of my life.

“Every time I hear Jeff singing, he reminds me of the strength I found in the most vulnerable time in my life. For that, I am grateful.”

In that first interview with Inpress, Buckley revealed his desire to write a new American national anthem. “I hate the national anthem,” he declared. “The song itself is about having kicked somebody’s arse in war with bombs and stuff. Someday, there will be a [new] song, and hopefully, if I live into old age, I’ll make a stab at it.

“That will be my crowning achievement if I can replace that awful thing called the national anthem.”

He also said he hoped that Grace would be timeless. “If I make it into old age, I’d like to be able to visit it and have it still be true. The things I love the best are very timeless.”

Buckley highlighted Bob Dylan, Patti Smith, Duke Ellington and Allen Ginsberg. His favourite Ginsberg poem was Kaddish, which includes the line:

And how Death is that remedy all singers dream of.

Sadly, Jeff Buckley didn’t make it to old age. On May 29, 1997, while in Memphis working on the follow-up to Grace, he went for a swim in the Wolf River. His body was found on June 4.

Jeff Buckley never got to write that new national anthem. But one of his wishes came true: Grace is timeless.

In that first Australian interview, Buckley mused about his second album. “I’ll make an album that’s so not me,” he predicted. “But it will be me.” He even revealed he had a title for the record: My Sweetheart The Drunk.

The posthumous album Sketches for My Sweetheart The Drunk was released the year after Buckley’s passing.

“The songs that would have been My Sweetheart The Drunk (as well as all the other recorded material he left behind) are the true ‘remains’ of Jeff Buckley, not the speck of dust that was pulled out of the Wolf River,” his mother Mary Guibert said.

The Sketches album entered the Australian charts at number one. It was Buckley’s first number-one anywhere in the world.

Guibert also compiled the 2000 live album Mystery White Boy, which included five songs from the Palais Theatre in St Kilda, as well as Buckley’s cover of Big Star’s Kanga-Roo, recorded at Sydney’s Phoenician Club.

The great tragedy of Jeff Buckley and the modern music business is that Grace was his only completed album.

In the liner notes for Sketches, Bill Flanagan wrote: “If the music business ran in the ’90s as it did in the ’60s, Jeff would have had five albums out … But Jeff loved searching more than arriving.”

By the time Tim Buckley died, aged 28, he had released nine studio albums. Jeff, who died at 30, released just one.

But then, we were blessed to have experienced Jeff Buckley’s genius. One perfect album and some magical live shows.

Hallelujah.