Bad Religion

Bad ReligionA short phrase written in memory of someone, usually as an inscription on a tombstone, is known as an epitaph. But what the term commonly evokes in the minds' of alternative music lovers is the vast catalogue of the label of the same name. When Bad Religion's Brett Gurewitz founded the small indie label back in 1980, maybe he was paying tribute to a close friend or family member who had passed away. Today, however, the label's name more appropriately relates to the dying genre it once exclusively played host to.

“In the beginning, I thought it would just be a punk label, and I didn't plan more than three years ahead, and I never have. But the time came when I had to sign something else…punk rock, in terms of the punk rock that Epitaph had been doing in the mid '90s, had sort of become mainstream rock, and I was not in the mainstream rock business. We're an indie label, and so that was sort of out of my league to do that stuff. Underground punk bands were just selling nothing, so if I put those out I just wouldn't have a business, and all the people that work for me would go hungry and their children would die.”

Punk rock isn't what it used to be, but luckily Bad Religion dug their claws in deep when the genre was at its prime, and to this day, as they enter their 33rd year as a band, are still reaping the benefits.

“Nobody likes this kind of music anymore,” Gurewitz speaks of punk rock. “The people we're selling records to are not 16-year-old kids - maybe a few, I mean, don't get me wrong – there's a few kids that like their dad's music or something,” he laughs.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

“The thing that makes a punk band different than the kind of music that's happening nowadays is you have to be able to play – you have to be able to pull it off live and be motherfuckers onstage. If you're some screamo band, or dubstep band, or something like that, then it's all programming, it doesn't matter, you can go up there and do karaoke. But in a punk band, you have to play your instruments like a motherfucker. And to do that you can't keep breaking up and changing members and all that.”

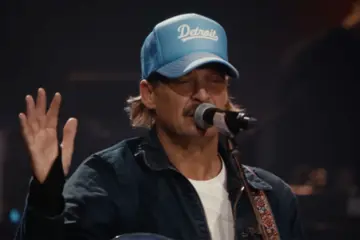

Although Bad Religion has had their fair share of line-up changes over the years, the creative core of the band has remained the same for the most part. On two occasions Gurewitz stepped back from the band to focus on Epitaph, firstly from '83 to '86, and again from '94 to '01, but always found his way back – even if he isn't a touring member of the band anymore. While he shares songwriting duties with frontman Greg Graffin, he hasn't actually toured with the band since a European tour promoting the band's 12th studio album, The Process Of Belief, in 2002. So if you've seen Bad Religion at any point since 2002, you wouldn't have seen Gurewitz. “I don't look at it as one side of things. I'm lucky that I get to still be in the band and have a label and get to do lots of interesting things,” he tells.

Although it may seem like a somewhat unorthodox way of running things, their formula is working. The latest release through Epitaph is the band's 16th studio album, True North. The album sees them doing a complete circle and returning to their roots with 16 songs crammed into 35 minutes. And although they've recreated an album with a similar feel to their earlier material, they're in no way recycling and regurgitating old riffs or melodies. “It was the record Greg and I wanted to make, and I think maybe it felt a little bit like we had lost the plot on the last album, if not lyrically, maybe musically,” he admits.

“We really remembered the things that were driving us in our heyday, you know. Things like making sure there's no bullshit in the song, making sure that the chorus is hard-hitting, making sure that the message is honest, making sure that there's no fat on the bones, making sure that the intros aren't indulgent – that they pull you in, but then you're hit with a chorus before you've got time to think. All the sorts of things that we thought made punk rock better and more exciting than the bullshit rock that was happening when we started the band. Sometimes when you've been doing it a long time, you lose sight of why you did it in the first place, and I think this time we remembered, so I think that's what made the record good.”

Returning to the songwriting style of 1988's Suffer and 1989's No Control is only part of the reason True North feels like the early days of BR. When they rocked up to the studio to begin fleshing out True North, their co-producer, Joe Barresi, had just picked up a two-inch tape machine and some tape for his ever-growing collection, and mentioned it could be an option.

“We weren't really connecting that with the idea of, 'Well, we're making an old school record, let's record in an old school way.' But it sounded like fun and we had made most of our records that way, in the old days…I think there's something [really cool] about tape. I'm not one of these purists that say you have to do it that way, but it gives you some freedom because it takes away a lot of choices. That might sound like a contradiction, but you're just going to play it as good as you can when you know you're on tape. You're not worried about recording it, and moving it around, and adding all kinds of bullshit to it, so you put everything else out of your head and you just play as hard as you can.”

With most of the band around their 50s, it's not uncommon to hear them joke onstage about putting their backs out or rattling off dad jokes about younger bands or more interesting genres at festivals. All it takes is a sarcastic comment from Graffin hinting that whatever record they're currently working on might be their last, and fans worldwide go into panic mode and the internet is overruled with news posts about the band calling it quits.

“We're so fucking old now that we keep making records and everyone keeps thinking it's our last. Especially if you make a good one, then they really think that. Although, this one seems like it was a particular good one. I feel it's very successful artistically, I don't know if it will be successful commercially, but that doesn't really matter to me at this stage of my career.

“The band is really happy with the record, and so, when you make a really good one, of course it's tempting to say you want it be your last, but I don't think we can do that. Honestly, I don't know what could cause us to stop making records. We enjoy it too much, you know. When we go a little while without doing it – without writing or recording songs – Greg and I start to yearn to do it again. It's not like we're dependent on it for our livelihoods – he's a professor and I'm a business owner, so we're doing it for love, we're not doing it for money. So I don't see why we'd ever have to stop.”