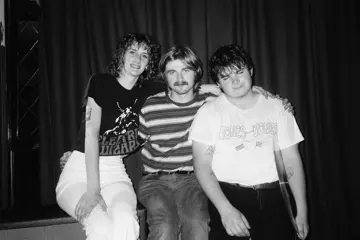

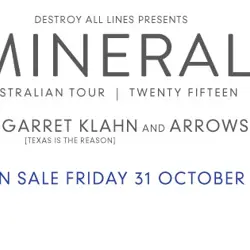

Mineral

MineralAbout 20-odd years ago, an impassioned musical revolution was taking place in all corners of the United States, its seeds sown in the frenetic, unkempt, do-it-yourself energy of punk rock and hardcore, with lyrics and vocal performances born of heartfelt honesty and unashamed, sometimes physically violent, catharsis. The burgeoning subgenre became known as emo.

Prototypical acts such as Californian three-piece Still Life, Washington DC’s Rites Of Spring – who rejected the term – and New York City natives Jawbreaker broke the first ground in the mid- to late 1980s, though the second wave in the ‘90s would be when the movement would truly come into its own, as soon-to-be indelibly influential bands that would come to be identified with the tag (including Jawbreaker, who hung around until 1996) broke through in all corners of the country, from Seattle’s Sunny Day Real Estate and recently returned Illinois outfit Braid to New York’s incendiary Texas Is The Reason and – importantly, for the purposes of this review, which is definitely coming after this little history lesson – Austin-via-Houston-based trailblazers Mineral.

It all fell to shit in the 2000s, when the term broke into the mainstream and became a catch-all label for every angled-fringe-sporting, black-clad teenager who happened to like My Chemical Romance or Taking Back Sunday – but since the whole thing dropped out of favour, there’s been a grassroots revival and return to the sounds steeped in the second wave, those ‘90s heroes who found renewed life when teenagers at the turn of the century were discovering Napster and secondhand CD exchanges and finding ways to hear and be influenced by then-little-known, long-gone bands they’d never have heard otherwise – and some, like Mineral and Braid, have been given fresh cause to return two decades after their prime to connect with the audiences they never even knew they had.

And, man, listening back to The Complete Collection – which is comprised of only two full-length albums, The Power Of Failing and EndSerenading, both coming in the final two years of their blistering four-year career – it’s more obvious than ever just how big an impact they made on the bands now thriving under the emo umbrella, halfway into the 2010s, which makes this release perhaps more relevant than ever. So let’s jump back 20 or so years.

Disc One: The Power Of Failing (1997)

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

Given Mineral’s subsequently seminal place in the genre’s history, Five, Eight And Ten, the opening track of the Texan emo pioneers’ debut album, The Power Of Failing, is a particularly rare type of song. It quite literally has come to serve as an introduction to a movement, so crystallised across its restless five-minute run time are the aesthetics and values of the scene. It is – in the best terms possible – a perfect blueprint for how to write an emo song.

Creeping in on quiet, clean-channel guitar arpeggios, restrained percussion and frontman Chris Simpson’s ever-so-slightly wavering vocals, it slowly builds its elements – a crash cymbal splashes here, a slightly overdriven guitar chimes there – until, a little more than a minute into the song, it all explodes. The drums pick up; the dual guitars intensify; Simpson’s vocals crash up an octave or so, all mildly adenoidal and hovering around, never quite on, his intended pitch. But it doesn’t matter – the emotive sum of these parts trumps by far any musical imperfections as the track bursts and blooms and works out its sadness in an alternatively introspectively quiet, loudly extroverted way before quasi-peacefully settling on some kind of hopeful note.

Perennial favourite Gloria follows, inverting the trick to come crashing out of the gate all discord and squeals before pulling back for Simpson to pessimistically warble, “A brave morning/Thoughts flap their wings and fly/And I can still taste/Defeat on my lips,” before the song opens up to navigate its swells and surges on the back of drummer Gabriel Wiley’s faultlessly shifting tempo work.

Indeed, it’s not just Simpson and guitarist Scott McCarver who get to shine – Jeremy Gomez’s bass work is given focus in the intro of the driven 80-37, throughout which he manages to capably straddle the divide between rhythmically ‘holding the fort’ (to which he is relegated in the slowly intensifying tide of otherwise-highlight If I Could) and letting himself have a little fun, as well as in Slower, all strummed chords before some dextrous work in the chorus and bridge, while Wiley proves himself a broadly talented drummer at pretty much every turn. He easily tackles spasmodic bursts into driven rock-outs (July) as well as subdued, atmospheric and metronomic backing beats (the solidly down-tempo Silver) and technically impressive tricks such as penultimate track and late-placed standout Take The Picture Now’s delicate, minute-long introductory snare roll before the track’s heart-rending final chapter gives way to the quietude of album closer Parking Lot, with its strained, slow build-up and shrill refrains lifting Simpson’s ultimate lamentations towards the record’s sonically energetic, determined resolution.

This special edition version of the album comes with a fistful of goodies after the original endpoint – previously unreleased cut Sadder Star kicks out one final fresh downcast jam before alternative versions of the album’s most enduring – Five, Eight And Ten, Parking Lot, If I Could and Gloria – provide a novel insight to round out proceedings, but it’s easy to see why the versions that did make the cut were chosen over the slightly rougher-hewn B-cuts.

It’s not a perfect album – in fact, it descends into outright cacophony at times – but, in a way, that’s kind of the point (the clashing disharmony under bone-shivering vocal howls during the back half of Dolorosa soars as a wonderful example). The Power Of Failing is, for all intents and purposes, a purge – of baggage, unsaid words, attachments, vulnerability – in order to be able to carry on despite the heartbreak and harrow of the preceding ten (original) songs, and it’s clear, in the exhausted aftermath, that the power of failing, perhaps, is not in its being twisted into a reason to give up, but our capacity to use our shortcomings and missteps as a reason to pick ourselves back up and keep walking.

Disc Two: EndSerenading (1998)

Though coming only a year or so after their boundary-challenging debut, Mineral’s second and final long-playing album, EndSerenading, finds the four-piece astoundingly matured in comparison with the unbridled outcries of The Power Of Failing. Opener LoveLetterTypeWriter forgoes the soft-loud-soft-loud dynamic that reigns throughout the previous album, instead clinging meekly to loosely duelling guitar lines that dance within a tonal third, or maybe a fifth, of their root note. Above the meandering strings, frontman Chris Simpson demonstrates a now-iconic technique found throughout the vocal work of fourth-wave revivalists from Joie De Vivre to Empire! Empire! (I Was A Lonely Estate) – the bending and stretching of syllables to near-untenable lengths, filling the song’s almost-four-minute run time with a grand total of six lines of prose; it takes nearly a minute for him to utter the initial stanza, “Summer unfolded like a tapestry/And you were there as you have always been.”

It’s a bold move to start an album on such a restrained note – no drums to speak of, no real point of difference between its beginning and its ending – but in some ways the wistful reflection and backwards-looking nature of the song’s lyrics – which come to rest on the rumination, “Will you ever know how much I love you for that?/Will you ever know how much I love you?” – are just as circuitous, which helps the whole thing work as a captivating entry point despite never really going anywhere.

Second track Palisade, finds Mineral returning to a more traditional dynamic set-up, though the initial restraint of LoveLetterTypeWriter lingers on, the song never quite unleashing on its audience with the same kind of ferocity that permeated so many of the band’s earlier songs. In fact, this is where Mineral’s meteoric jump in maturity is so obvious – in the decisions they make to hold back where they might previously have blown up – the snare roll-driven build of Gjs approaches the brink of bursting several times before finally loosing itself of shackles three-and-a-half minutes in, while more-than-six-minute (but less-than-six-line) highlight Unfinished perhaps ventures closest to TPOF territory with its climactic wails as Simpson dreams hopefully of “December, dancing together with rings on our fingers/And the two shall become,” leaving the final lyric one word short of any real sense of finality.

For Ivadel marks a rare, consistent stepping up of the tempo as all parties lift their game to deliver a solidly driving arrangement overlain with noodly, almost jangly, guitar lines, before Waking To Winter evokes a deliberate, if mild, air of discomfort in its slightly detuned string work and Simpson’s less-than-stable (by design) vocals.

ALetter, like Gjs before it, marks a return to a slightly heightened sense of raucousness between its more thoughtful sections, while dreamlike standout Soundslikesunday plods determinedly to its diametrically optimistic conclusion – “How blessed we are for crying now/For we will laugh someday, and how.” Pseudo-title track &Serenading does a lot with relatively little, the scarce soundscape and Simpson’s elastic vocal work emotively holding the song together through five-and-a-half down-tempo minutes, while lush closer TheLastWordIsRejoice brings the official journey, older and wiser and less prone to outburst than its predecessor as it may be, to a deeply fearful, uncertain end, one that could only have been informed by the increasing listlessness and disaffection thrust upon a struggling group navigating their 20s and the frustrations of getting older and less safe, one year at a time.

Like The Power Of Failing before it, The Complete Collection’s EndSerenading comes with a handful of bonus tracks, though all five – Rubber Legs, February, M.D., Love My Way and the truly wonderfully disharmonious Crazy – are taken from limited or otherwise rare releases, and though none of them necessarily offers anything, thematically or aesthetics-wise, that hasn’t already reared its head over the course of Mineral’s discography, they do raise questions about what the band could have been capable of had they outlasted the ‘90s and capitalised actively on the growing culture of the internet in the early ‘00s.

Then again, given how the entire scene turned in that era, perhaps it’s for the best that, for now, we only have this album and the one before it to protect and maintain the legacy of Mineral – and their influence on an entire generation of musicians.