As the crowd laboriously milled into the Odeon, the elders welcomed us with burning paperbark and a branches of black peppermint. "It's to cleanse you of bad energy," the man said to us, cooling our white hot hangovers from last night's afterparty with a dab of ochre to the forehead and the familiar sweet, smoky smell of bushfire.

Three striking figures each with an amber spot wash, made almost dusty by the light rolling smoke across the stage. Their appearance is clean — white shirts with black trousers and ties. Faces, obscured by overhead lights, hung dark and pensive behind the smoke and shadows.

Pensive vaguely upbeat synth lines like notes on a compressed church organ melded with strong bass-heavy desert and didgeridoo rhythm patterns, with the light minor chord plucking of an acoustic guitar woven delicately between a tumbling stream of the digital pops and clicks.

The instrumental composition True North was a journey. Enhanced by the visual clip show that thanks to dynamic editing did not feel as kitsch as such ambitions often do. Overutilised nature art slide shows have long been a tradition in live instrumental performances, but here its curation of nature shots of trees, grass, clouds and bees seemed fitting.

Halfway through the show MONA's David Walsh walked in and sat in front of us, his signature grey hair and eclectic wardrobe noticeable from anywhere. His eyes held stress lines that seemed just as likely made by play as work. Over the past six years he has missed perhaps only a handful of MOFO's multitude of events, and the signs are telling. The reward he gets for giving Hobart a gift so grand may perhaps never truly be repaid.

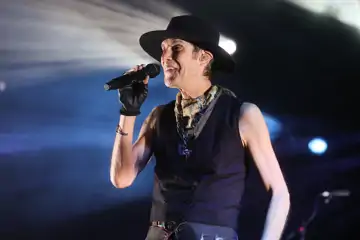

Tim Moriarty with his guitarist and keyboardist move silently to the front of the stage. the synths pulsing so dramatically and theatrically you could close your eyes and feel the scramble: the red ochre clay clumping under your nails as you crossed a cliff face, a forest that can only be created by punishing sun and red dust sprawling below you, the dry chalky taste of earth in your throat and the heat of the sun on your right shoulder, as you head True North.

Thirty minutes in the performance ends and the show meets its interval signified with one last guitar note playfully plucked above the synths dying hum — the music equivalent of the purposeful silence after an awkward joke.

There is a break as long as the first performance until the house music is punctured by the slow and purposeful minor notes of a piano. A singer starts to sing while on the screen behind her worn, calloused hands separate blades of grass. A bass player and a drummer punch in as the singer hits a strong, long-held note. A major key change accompanied by a straight eight rhythm with a three-beat kick.

A second singer walks out and joins for the chorus, strong harmonies dripping with pop and gospel influences as the two women stretch out their hands to a crescendo of applause. These are love songs to the earth. These are hopeful stories for future people built to step from shadows of a tumultuous past and present. The screen in the second song projects a series of high definition portrait clips of Indigenous Australians in communities rural and urban. These are the Songs Of The Black Arm Band. "I have something to call my own, these are my children and this is my home."

Joined by a man with a voice that could draw a tear from a stone the three singers delivered a powerful story of the Stolen Generation that weaved from its beginning to its end. To whooping applause the three left the stage and an instrumental full band song led by didgeridoo was played in front of images of the long grass.

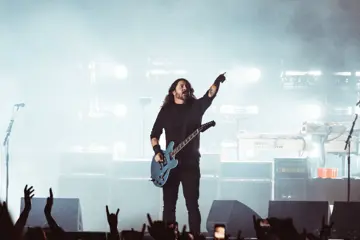

The man returns alone beating rhythm sticks like wood cigars and he sings a song in language older than English; half-facing the crowd he moves his body slowly and purposefully across the stage. Returning to a full band sound the group performs an earth-shattering rock number about standing on sacred ground and living on borrowed time, replete with a solo on electric guitar. The singers share a grinning embrace and the man departs.

The guitarist leads with a melancholic melody of rising and falling scales before the voices join in on a sweet mournful harmony set to scenes of birds in flight. As the women stand in the centre of dropped cones of golden spotlight, the stage is pulled to black.

Tasmania has a particularly savage history of mistreatment of the Indigenous population. The music is good but the stories contained within them may be carried much longer by the audience.

Songs Of The Black Arm Band adds another voice to a conversation that is older than our fledgling nation and is far from complete.

In the final moments of the show the stage is blacked out and the singers take turns to whisper, eventually shouting and interrupting each other for powerful dramatic effect; a flood or orange sky then lights the screen and as blue washes flood the band the singers lift their voices — rich, sustained and powerful — to one final crescendo, the crowds rise, and their feet clap like thunder.

The standing ovation is treated to an encore rendition of Kev Carmody's From Little Things Big Things Grow, the new generation paying fitting tribute to the songs that shaped ten years of The Black Arm Band.