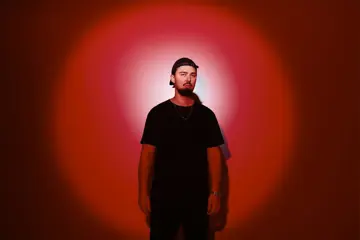

Violent Soho

Violent SohoNot even in their wildest dreams did the four friends who make up Brisbane rock behemoth Violent Soho predict the wave of adulation which embroiled the band following the release of 2013 album Hungry Ghost. Years of toil and dedication to the cause came to sudden fruition when that album’s defiant reverie touched a nerve with thousands of new fans, transforming their gigs into swarming seas of shouted refrains, flailing long-hair and vast vistas of Soho t-shirts and merchandise.

“All of the articles from around that time were pointing to EDM and artists like Flume really taking over – and we saw that last year with Flume and Chet Faker doing so well – and it was just like that when Hungry Ghost came out,” recalls frontman and chief songwriter Luke Boerdam. “We had no inkling that all of a sudden this whole generation after us would pick up this record and really get into it.”

“And it didn’t get mega reviews or anything either by any means,” reflects guitarist James Tidswell.

Boerdam: “I was so stoked when we sold [450 capacity Brisbane venue] The Zoo out and then a second one [for the Hungry Ghost launch], and then I thought, ‘Well that peaked!’ I honestly thought that was the only tour we were going to do and then we might do a festival like Falls, and I remember when we did play at Falls we had a worse playing time than we did four years beforehand.”

Tidswell: “We were on two hours earlier so it was a dramatic change.”

Boerdam: “And we thought, ‘This is the reality of where we still sit in the scheme of things’”

Tidswell: “We thought it was awesome that we can still play festivals at all.”

Boerdam: “It was, like, ‘Wow, we still get to do this! How awesome is it that we’re back here?’ Then we walked out onstage and there were thousands of people singing every word, and we thought, ‘Okay, maybe this album has a life of its own that we haven’t seen yet.’ So yeah, we were shocked.”

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

But whilst Violent Soho may be (fairly) renowned for their ‘party hard’ approach to life their consistently fierce work ethic as a collective continued unabated, the countless festivals and headlining shows they played in the 18 months following Hungry Ghost’s release expanding this rabid new fanbase even further. So when it came time to craft what would become their next album WACO they initially decided to take a new, ‘more professional’ approach, before coming to the realisation that if something ain’t broke then there’s no point in fixing it.

Boerdam: “I wound back my work hours to focus just on the band, and I overconfidently thought, ‘Great, now I’ve got all this time and I’m going to approach it like a job, and I’ll write nine hours a day and I’ll turn over a record in three months’. We met up at the beginning of 2015 once all the touring was done, and I was, like, ‘Oh yeah, I’ll have a record done in four months don’t worry, I’ve got all this time to sit down and write’. James laughed at me, he goes, ‘Are you sure?’ And I was, like, ‘Trust me man, I can write it.’”

Tidswell: “It was January and the release date was meant to be in July. It wasn’t that I didn’t believe him, it was just dramatically different from the way that we’d done things before.”

"Just do what your band is good at doing and just do what you want to do and fuck off any external pressures or anything around you."

Boerdam: “I should have known that music’s never easy, ever. I delivered two tracks in four months that I was happy even showing the band, so there’s that reminder of the way that I write – and also the way that the band works together – is that we like to do things organically. Luckily we chose to work with people like [Soho’s label] I Oh You and all the people around us who know that we’ve worked that way for nine years when they signed us, so there wasn’t [any expectation] for us to turn it around super quick because we’ve got this big record behind us now – we stuck with how we’ve always worked – so when I did show up with just two tracks we allowed ourselves more time and worked out a plan where we could still have another six to eight months of writing on top to organically work through another record we were happy with. So there was a bit more pressure on Bryce [Moorhead] as a producer – I know he felt the pressure because to his own level of expertise he wanted to make it sound better – and there was pressure on ourselves to make a better record than Hungry Ghost: even if wasn’t a popular record we still would have wanted to make a better record.”

Tidswell: “After putting everything what we had into the [2010] self-titled album and getting the response we did, what happened with Hungry Ghost was so dramatically different and we really got to see both sides of what can happen no matter how you feel. As much as you’re afforded the opportunity to buy into what makes an album [successful], we really focussed on just allowing Luke as much time as possible and allowing each other to make the album we wanted to make.”

Boerdam: “To do it any other way would be ignoring the lesson of Hungry Ghost, which is just ‘do what your band is good at doing and just do what you want to do and fuck off any external pressures or anything around you’. Because Hungry Ghost was really like a last hurrah for us, and we were, like, ‘No, we’re going to do it in Brisbane and do it the way we want to do it’. So to do it any other way and listen to those pressures after nine years of… not failure but nine years of not exploding, would have been to ignore everything we’ve learnt.”

Soho don’t believe that this lesson they learned – that an album recorded comfortably at home can do as well as an album recorded overseas with a big name producer (Violent Soho was recorded in Wales with the renowned Gil Norton at the helm) – is strictly universal, rather feeling that all bands are faced with a different set of circumstances to adapt to.

Boerdam: “I think it’s different for every band, personally. I think bands are better off taking the most honest approach for them, and for us that’s working with a local producer that we can spend as much time as possible with – that works great for our band. And we just personally get along with Bryce so well, so that’s what works great for us. I think it’s proven that you can use a small studio down the street and still have a record that goes gold. I mean so many other records have proven that it doesn’t need to sound a million bucks to sell loads of records, it just doesn’t.”

Tidswell: “And it’s a record by record basis as well – these two records would not be able to exist if it hadn’t been for [Brisbane studio] The Shed and Bryce Moorhead in terms of being able to be recorded. It wouldn’t have been able to happen the same way. I mean what would we have done for Hungry Ghost? Goodness knows.”

Boerdam: “And it really comes down to time, I don’t know where else we could have got Hungry Ghost done, a record like that. But yeah, the more time we can give ourselves in the studio we’ll squeeze every little bit of that time to make it sound the best it can sound really. If you go overseas and work with Gil Norton you’re only going to get three weeks. Some bands can do that and it’s good for them, but with us we just like that organic, slow approach. Really slow. This time around was really, really slow.”

When Boerdam was locked away treating the writing stage for WACO like a day job but ultimately unhappy with the results, was he producing material that he wasn’t happy with or were no songs coming at all?

Boerdam: “I was producing some results but I just wasn’t happy with the results – they were either bland or too similar to stuff that we’d done already. I throw out a lot of stuff. I write in pieces – a riff here and a riff there, and pieces of lyrics here and there – and it’s more those ideas that you throw out, like, ‘That riff, you know what that sucks’. It was weird, the lesson I got from it was ‘the more I tried the more it didn’t work’. I did all these weird things like put on Ken Burns documentaries on half volume so you can hardly hear it and just muck around on guitar that way, and that would produce way better songs than if I sat there intently going, ‘C’mon, where’s the riff? Where is it, where is it?’ It just doesn’t work that way, especially if you have a somewhat slacker sound. It makes sense.”

The two guitarists explain that rather than trying to expand the band’s sound they preferred to try and stay true to what had made Hungry Ghost so appealing.

"I did all these weird things like put on Ken Burns documentaries on half volume so you can hardly hear it and just muck around on guitar that way."

Boerdam: “I think that was a good way to describe it, being true to what Hungry Ghost did and organically going further but not drawing a line in the sand and saying, ‘Well this song doesn’t go further so it’s off the record’, or, ‘This song kinda sounds like something from Hungry Ghost so it’s off the record’. I think that would have been a really horrible way to make another record, and it would have taken another four years really (laughs). So it was just like with Hungry Ghost, we threw out heaps of songs and were in a bit of a lull after being over in the States and it was the same thing of going, ‘Does this song excite us? Do we feel that this is stepping it up a notch?’ But I don’t think there was any agenda to go, ‘Right, we have to sonically take this further now and prove something’. I think we got sick of trying to prove stuff!”

Tidswell: “I think the songwriting approach may have come out of – and correct me if I’m wrong – protecting what we were, because obviously for the very first time in our existence of being a band we instantly found ourselves with thousands of people at the shows rather than hundreds. And we were very happy with hundreds, so you can imagine what it was like with thousands! And immediately the only rule when we regrouped was ‘let’s just stick to what we know’. Luke just literally started writing, and he’s probably being modest when he says that he throws out a riff here or there, sometimes they were entire songs [being thrown out] and they were good.”

While WACO naturally displays plenty of Soho’s brute force it’s definitely a mellower record in terms of tempo across the board.

Tidswell: “I think that the groove is cruisier, there’s no Love Is A Heavy Word. I think we’ve gotten older and more relaxed in how we play it. We still know how we want it to be heavy, but we’re more relaxed about it – there’s not that anxiety.”

Boerdam: “It’s not that hyped, punk approach where you’re constantly trying to speed up the tempo or something with vocals going crazy all over the place, it sits more in its place.”

Indeed WACO sounds sonically like it was chiselled out of granite – much credit due to Moorhead in that regard – but as a document it’s a perfect continuation of how Violent Soho embraced nuance and subtlety on Hungry Ghost without compromising the brute force that makes them such a powerful proposition. There’s some intricate musicianship and adventurous arrangements, but in essence it’s a more refined and confident take on the core Soho aesthetic.

Boerdam: “It’s funny because we had interviews when we released [WACO’s first two singles] Like Soda and Viceroy and some of the interviewers would say, ‘Oh, we’re so happy that you didn’t go all soft and electronic’, and I was, like, ‘You honestly thought that that was a possible outcome?’ So in terms of protecting what Violent Soho stood for I think that’s what was left to prove, that we can write another record that we think is great…”

Tidswell: “And not go mellow. I think there are softer songs, but by no means is it missing the heavier ones. And of course it’s going to be pulled back – we’re by no means the same individuals that we were when we did Hungry Ghost. That was three years ago – think about what happens in your life in three years – so including obviously the writing and then the playing of it and the approach to it, there’s the same people but just in different spots in their lives. So we can’t play a record like Hungry Ghost was played at that time, because we’re just not those people anymore.”

The men who make up Violent Soho may have changed as individuals in the time between albums but what hasn’t dissipated is the overt unity and camaraderie displayed by the foursome.

Boerdam: “You know we’re a ‘friends first’ band. That’s the label someone put on us once and it’s really true, if you go back to the core of the band when we started we were literally picking instruments for each other. Mikey [Richards] had played some drums and I was singing and writing songs and stuff, but [Luke] Henery was, like, ‘Oh alright, I’ll play bass then’ and that’s literally how the band started. So if you go back to that core it kinda makes sense that it’s worked for all these years because we’ve known each other so long. I’m never going to judge James if he’s, like, ‘Oh I fucked up a guitar riff tonight’, I’ll be, like, ‘Dude, when I met you I could play two chords. I don’t give a fuck if you stuffed up!’”

Tidswell: “The amount of forgiveness we’ve already had to go through in 14 years means that there’s nothing that could cause us any actual problems.”

WACO continues Violent Soho’s learning curve of using the studio as a weapon, with each of their releases to date having bettered its predecessor in terms of making the most of their surroundings.

Tidswell: “Luke certainly has got better in that regard, he’s lived in [the studio]. When you live in something you’re naturally going to get better and that’s definitely happened with Luke.”

Boerdam: “But there’s also things like we got a band room for the first time – our own personal space – and Mikey and all the dudes have been in there, so I’ll be at home learning how to make demos and getting into audio engineering and stuff, and meanwhile I’ll be sending demos over and Mikey would literally drum over them for days before we’d even hit the studio. And same with Tidswell and Henery just going through their guitar and bass parts.”

Tidswell: “[Mikey] would do a section of the song about 17 times, to the point where it would drive me so crazy because I need to listen to the whole song not just his little drum fill. But I guess everyone focussed on nuances in their own way.”

Boerdam: “We’ve never been one to focus on technical ability, it’s not in our sound, but I think there has been a jump [on what we’ve achieved in the studio]. I could hear it too when Mikey was drumming, he was adding little things like hits on his ride cymbal. He did so much stuff on his ride that me and Bryce were looking at each other saying, ‘Well we’re not using that but we’ll let him have his fun’, and then we actually used it and he’d added all these little parts that made it awesome. On Hungry Ghost we didn’t have that, we were all working jobs so we just rocked up and made this album, whereas this time around all that pre-studio work paid off.”

And this time around they were also still writing up until this pre-production stage.

Tidswell: “With Viceroy, the very first time that Luke sent through the demo of it would have been the end of November – that’s how fresh we’re talking, it’s already out!”

Boerdam: “We had dudes in the studio interviewing us and asking, ‘Where’s this record going? What’s the meaning of this record?’ and I’m, like, ‘Dude, we haven’t even finished fucking writing it yet!’”

Yet despite this apparent fervour the WACO sessions were by all accounts still a fun affair for the band.

"I think with WACO I liked it aesthetically as an album name because it feels like it describes this really far off place that’s this distant, weird land."

Tidswell: “Yeah I reckon [they were a good time]. I know Henery hard a really tough time one day – and I’m only saying that because Henery has made mention of this day – but apart from that I think everyone at most times was having actual fun. We’ve never gone to the extent of having a Playstation there before and that sort of thing – it felt relaxed. I think people had practiced – which is something that I certainly hadn’t tried before! I used to try, but never practice.”

Named after the Texas town where the Branch Davidian cult – led by their messianic leader David Koresh – held their deadly showdown with US authorities in 1993, WACO thematically continues Hungry Ghost’s examination of the malaise and alienation that Boerdam believes so plagues modern society.

Boerdam: “There’s not a really clear, super-distinct line between the two [albums], but when I listen back to the record and try to glue together the picture I know people are going to ask me about, I just kind of picture WACO as Hungry Ghost’s older sister, kind of in the hallway peering into the door because it’s darker. Hungry Ghost kind of scratched the surface of this false reality, whereas I look at WACO and think, ‘Yeah, it scratches that surface even deeper, but really gets into the nasty stuff of how humans are so easily tricked and how and what these illusions are that make us feel that we have control over everything.

“I think with WACO I liked it aesthetically as an album name because it feels like it describes this really far off place that’s this distant, weird land – it gave the album an identity and was dark – but as a metaphor I liked it because these people created their own reality and couldn’t deal with the world how it was. They were, like, ‘[Koresh is] Jesus Christ, this is the Second Coming, and we’re willing to kill ourselves for it’, and it was this really dark world that they’d created for themselves which made them feel better and gave them control over everything.

“I hate going into heaps because I don’t want to sound like a pseudo-intellectual or something, but when I think about where it’s come from those are the things that excite the most talking about it and singing about it, because I feel that it’s scratching away at the truth and trying to put some words with the music on what are these places that we’ve created for ourselves and how humans deal with it. Hungry Ghost felt a bit more light-hearted – some songs were just about getting high and escaping; escapism – whereas with WACO I feel it’s more looking at the human side of it and really describing those emotions and trying to paint that world and paint that vision that everything around us is much darker than we realise.”

Did Boerdam’s empathy with the Waco situation lay in the fight itself or how far they were willing to take it?

“I think if Dean was around he’d have a big smile on his face and he’d be saying to a lot of people, ‘I fucking told you so!’"

Boerdam: “I think how far they took it. It’s a crazy story and there’s countless metaphors and stories you can pick but that one was incredible, how it started as this small stand-off and blew into this part of America’s history which is really dark. The stand-off went for something like 50 days – it was ages – and also the way it wound up was kinda eerie: there was the fire where people ended up burning and to this day it’s unknown where the FBI started it or if they did it to themselves. In both situations that’s an extremely dark conclusion, either way. And like I said I was drawn to the fact that Waco as a town has a super dark history stretching back to the Civil Rights movement and through stuff that happened then right up until the ‘70s – I’ve never been there but it seems like a dark place. Plus the name just works aesthetically [as an album title]. How To Taste, the opening track, that was the working title for ages because that seemed relevant as well.”

Tidswell: “That was the name almost the whole way through the recording and everything up, but when it came to the artwork WACO just worked.”

At the recent Melbourne leg of Laneway Festival Violent Soho were delighted to play the Dean Turner Stage, named for the former Magic Dirt bassist who managed and mentored the young Brisbane band before tragically succumbing to cancer in 2009.

Boerdam: “I think if Dean was around he’d have a big smile on his face and he’d be saying to a lot of people, ‘I fucking told you so!’ That’s exactly what I think.”

Tidswell: “And I don’t think that he would’ve believed that [our success] would be to this extent on our own terms. He was from the Melbourne scene and knew how it all worked whereas we were to some extent oblivious and just saying, ‘Nuh, we can’t do that’. He understood a lot more so I think he’d be doubly stoked.”

Boerdam: “In those earlier days he tried to get us signed early on, he got [Michael] Gudinski in front of us and [Steve] Pav and some others as well. Straight up when he started managing us he got some labels in front of us and said, ‘You’d be nuts not to sign them’. They didn’t, and we thought going independent was a pretty good route to go anyway, but I think if Dean was back he’d say, ‘Told you so! I saw something in these guys so long ago’. I’d like to think that his approach to music and what bands should be – his legacy and what he was about – lives on through our approach and things like Tym [Guitars]’ Big Bottom guitar pedal. All of the things he left around and all of the people he influenced, that’s why he’s got the stage at Laneway named after him because he was that guy. We went to his funeral and it was packed with so many awesome musicians who appreciated his impact on Australian music. Obviously he had a huge impact on us personally – I spoke to him every second day about songwriting and he just put so much confidence in us that this was something worth pursuing and that it’s going to get tough but you just don’t give up. As we’ve said so many times Soho wouldn’t be Soho without Dean Turner. Especially when we were forming – those formative years when you’re trying to work out what to do and how to approach it – he was the guy, he was the mentor.”

Tidswell: “It was his last few years of life and he shared a lot of it with us. He had a family but he still spent a lot of his last year with us to ensure that we stayed a band and that we’d approach the band the right way. We would never want to do anything that would differ from what he told us how to be, and I think that still impacts everything from our songwriting and approach to the fact that if we can’t practice we don’t practice – just being who we are without any pressure to do anything else. If it’s just a job then it will be guaranteed to suck.”