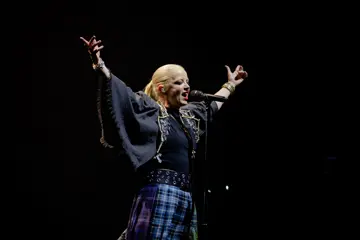

About a decade ago, Nadia Ackerman moved to New York to sing jazz. She packed her bags in North Sydney and moved to the big apple, found herself singing jazz standards, and then things changed.

“Long story short, I had a breakdown, an emotional, mental breakdown, about six years ago,” Ackerman says. “I did an EMDR, which is a rapid eye movement therapy, and when I came out the other side I started writing songs. I'd never written a song in my life so it was this hilarious situation where I was a jazz singer and I didn't write and then all of a sudden within the first year I'd written 350 songs.”

The first product of those songs was The Circus Is Back In Town. Originally released independently, it will be re-released after her next studio album. Ackerman kept writing and working as a session singer around New York. Most of the world might recognise Ackerman's voice from her work on commercials. The UPS commercial has taken her voice around the world and, as a major sponsor of the London Olympics, only continues to do so.

“I sing commercials, which is what you do in America while you're waiting for your record to take off. I've been living off UPS for two years. It's a worldwide campaign,” she says, “everywhere except Australia.”

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

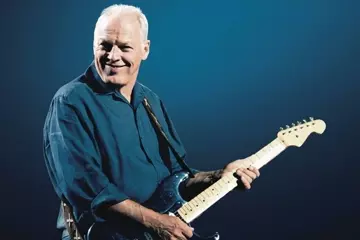

Beyond commercials, her day job is lending her talents to backing singing for major artists in New York, on one off shows or morning shows. It's a gig that's seen her appear alongside Sting, Elton John, Billy Joel, James Taylor and a whole swag of other big names. She recently sung at Sting's Rainforest benefit at Carnegie Hall for the fifth time.

“The first time I met Sting my mouth fell open,” she recollects. “I couldn't hold it together. He's a really good looking man, and really nice and really shy.”

The opportunity to work with some of the biggest artists in the world also provides a view into an otherwise mysterious world, where budgets aren't an issue and beyond the world of struggling to put together enough money to finish a record and then promote it.

“You get to see the truth of what's going on,” Ackerman says, “and you get to see how much money there is and you get to understand that they're people too. But you can really see who's a good person and who isn't. That's obvious straight away.”

Ackerman's art stretches beyond the music to a growing artistic portfolio. Her first gallery show was a week after we spoke. The music and art are connected in some ways with many pieces based on songs from her record.

“The strange thing is that it's connected, but I've been finding that when I'm drawing large bodies of work, I'm not songwriting. I'm finding that the parts of the brain that do the songwriting and the drawing don't function at the same time. And that's disturbing.”

Since she's been finishing the twenty-five artworks for the gallery show, songwriting has been pushed to the side. It doesn't worry her since she's already got the next record, and more, already written.

“I've written so many songs that I'm not too worried,” she says. “I've got my third record already written, that we're starting now. I've got a few records lined up, so I'm not too worried that I haven't written a song in two weeks.”

Ackerman's jazz background means she's used to cutting a record quickly.

“I usually work coming from jazz-land, where we go to the studio for two days and we all play live and we do the record in two days – seven songs a day. Which is a lot. We do three takes of each song and then pick one, and there's no cutting and pasting, it's straight performance.”

The Ocean Master was different, taking a year to record. It sits nicely between Cat Power and Feist with an alternative pop sensibility, on a bed of a minimalist but melodic arrangement.

This record took longer to record, “mostly because I didn't realise I was making a record,” she says. “The Ocean Master was different because I recorded a lot of it at home. I would do the songs as demos and they weren't demos at all, they were the real deal. My producer would record it here, say 'it's just a demo.' So we'd do the basics and sing and play piano in my bedroom and then we would start adding bits. We would have the cello player over and he would play his parts. The guitarist would come over and he would add his parts. So it was a situation where we built the record at home.”

The record explores Ackerman's journey post-break down, through struggle and triumph. She was determined that it would have that positive side to it, that triumphant side.

“I think the record is really about looking back and looking forward. There's a lot of shout-outs to my past, and struggles. Then there's triumph. It's a record that has to be listened to from beginning to end because there's a story of... not depression, but struggle, hope and triumph,” she says. “It's about coming out the other end of the breakdown and thriving.”

Even so, while recording the album she realised she wasn't quite through it all.

“There's a song on there called Underground that when I wrote it... I was out of therapy at the time, but when I wrote it I realised I had to go back, because I wasn't well. The record really does go through that transition.”

Although there's the struggle, it's the light at the end of the tunnel that Ackerman wants to focus on. That became a major point when it came to giving the album a title.

“It was going to be called In The Middle Of The Sea but then I thought that was a very 'poor me' title, like a victim. And I didn't want it to be like that.”

The title comes from her childhood on the north New South Wales coast. It was over a conversation with a friend about her late father's old fish and chip shop that the connection came.

“And I just went, 'Gasp, that's the name of the record'. It sounds like someone who is in control. The ocean is your emotions, so it's being in control of that.” She pauses. “Wow, I'm just working this out now.”