Little Steven & The Disciples Of Soul

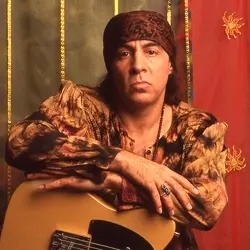

Little Steven & The Disciples Of SoulSteven Van Zandt – known widely in music circles as Little Steven, among other sobriquets – is something of a New Jersey renaissance man, yet he’s never been one to really seek the spotlight.

Whether it’s his long-standing role as Bruce Springsteen’s right-hand man in The E Street Band – it was Van Zandt himself who gifted him the nickname "The Boss" – or in his lauded TV role as Silvio Dante in The Sopranos, he’s usually happy playing sideman to bigger names, a role he carries off with a humble aplomb.

There are, of course, exceptions to every rule – he had the lead role in short-lived Norwegian-American gangster series Lilyhammer, and he hosts his own beloved Underground Garage radio show which is syndicated all over the world – but mainly Van Zandt is happy to eschew the limelight and leave the grandstanding to others.

But with The Boss a couple of years ago deciding to make a lengthy one-man stand on Broadway and his acting commitments having temporarily dried up, Van Zandt found himself reviving the ‘80s outfit he’d formed during another hiatus from The E Street Band – this time when Springsteen was assembling his 1982 solo masterpiece Nebraska – namely Little Steven & The Disciples Of Soul.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

His solo project had found him returning to the Jersey Shore sound that Van Zandt had helped formulate back in the ‘70s, first with his early group Southside Johnny & The Asbury Jukes and then on the early Springsteen records (which he largely arranged), and then over the course of a number of staggered albums taking that sound into new and routinely fascinating places.

Yet he’d barely even considered that body of work for 20 years when in mid-2016 he was randomly invited by a London promoter to appear at a UK blues festival, after which he pulled a new version of the band together and hasn’t looked back. Since then the band has two new albums to their name – Soulfire (2017) and Summer Of Sorcery (2019) – and has been touring ever since to global acclaim, something Van Zandt had never envisaged happening again.

“Yeah, it’s been quite an experience and I’m very, very happy I did it,” he chuckles. “It was fortunate, Bruce decided to spend some time on Broadway and I didn’t have a new TV show going, so just through those random circumstances I ended up revisiting my own work, and I found it to be really quite rewarding.

“I hadn’t realised the value of the stuff and how well it all held up and how it had kinda become its own genre through the years, that ‘50s rock-meets-soul thing which at this point is quite unique.

"It’s been quite a year-and-a-half of exploration and discovery."

“So it’s just been fun to revisit your stuff and try and reconnect with an audience again and see how the stuff holds up. It’s been quite a year-and-a-half of exploration and discovery and it’s been a very, very satisfying response from the audience – the audiences have been going crazy!”

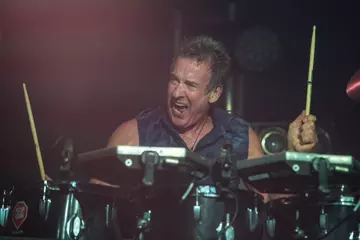

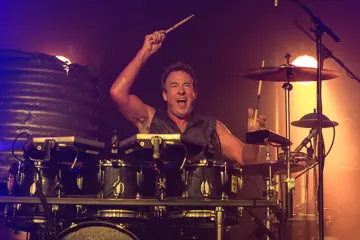

The Disciples Of Soul are a 15-piece powerhouse, but Van Zandt is like a pig in mud back putting their massive sound together.

“The arranging is the fun part,” he smiles. “I’ve been using five horns ever since we put together Southside Johnny & The Asbury Jukes really which was mid-‘70s, and then I carried that same sound into my first solo album in ’82. Then the rest of my solo albums are all very different from each other, so I just went back to it recently.

“Plus I recently produced an album for the great Darlene Love and she had these great background singers so I fell in love with background vocals, so that’s the one thing I’ve added to my sound now. I just thoroughly enjoy the horn parts and the string parts and the background vocal parts all being woven together and complementing each other, and making sure that they all work together and don’t step on each other and don’t cancel each other out and they all work dynamically: that’s the fun part for me.”

And being in the spotlight again? Little Steven is fine with it, but you can tell that he’s still taking on such prominence reluctantly.

“I’ve never really needed it, my inclination is to be behind the scenes,” he reflects. “I’m really a producer at heart – that’s how I describe myself. I really am a producer first, but I am a performer and I do enjoy being a sideman.

“Even as a frontman I got really quite good at it in the ’80s – you get used to it and you get good at it – and I’m almost halfway back to being a frontman, I’m not all the way there yet. I’m working my way back because it’s a big mountain to climb, man, it’s a whole different job and you actually have to work for a living as opposed to being ‘the guitar player’ where you can just muck around.”

Van Zandt is famously well versed in many different types of music – as well as the Jersey Shore sound he helped found, he’s a noted rock’n’roll aficionado and curates satellite radio stations covering both garage-rock and outlaw country – and he puts these disparate passions in part down to the timing of his earliest musical forays.

“I think growing up when we did, it was an extraordinary period of time,” he marvels. “It was an absolute renaissance in the sense that the greatest music being made was also the most commercial, which we’ll never see again or not for hundreds of years, I think.

“More than that, we were, in a funny way, pretty much a monoculture back then and the trends would come and go year by year: in ’64 everyone’s into the British Invasion, in ’65 everybody is into folk-rock and that’s when The Byrds and Bob Dylan started, in ’66 it might have been country-rock so everybody gets into country music and then it was jazz-rock so everybody gets into jazz, and then in ’67 it’s psychedelic-rock so everyone gets into that – and I mean everybody! – and then in ’68 blues-rock came in and everybody got into blues, and then the final trend of the ‘60s in ’69 was southern-rock, which is more rootsy and Americana and The Band and Delaney & Bonnie and Taj Mahal and The Youngbloods and people like that.

“And believe it or not most musicians would follow from one trend to the other and you’d pick up some pieces of it – you’d take some of it for your own identity – and then some would stay in it: some would get to country-rock and they’d stay there, some would get to blues and they would stay there for the rest of their career. But a lot of us would go from one to the next, and you’d learn that genre and pick up what you want from it for your own identity and then you’d move on to the next one.

“So I think partially it was a result of growing up in that time, when things went from one trend to another and we were all going to school without knowing we were going to school. Parts of each genre stick with you and in the end you tend to just appreciate greatness whenever you hear it, it doesn’t matter what genre it is really. Even if it’s not a genre that you’re particularly fond of or use for your own identity, greatness is greatness and you recognise it and you appreciate it. I think that’s what’s stuck with me all these years.”