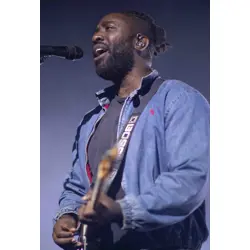

Kele Okereke

Kele OkerekeIn December 2016, Kele Okereke, the longtime frontman of English post-punk outfit Bloc Party, became a father. This has meant that in the past year he's spent more time tending to his daughter, Savannah, than anything else. But, in the middle of this run, he's also made an album. It's called Fatherland, no less, the title evoking both Okereke's newfound fatherhood and his Nigerian heritage. After his first two solo LPs - 2010's The Boxer and 2014's Trick - were built on electronic bangers, his third record consists of stripped-back songs written on an acoustic guitar. It's the most vulnerable and open Okereke has sounded, something echoed in the conversations he's having about it.

"Because of the title of the record, people have really homed in on this theme of fatherhood," says the 36-year-old. "But, to me, the songs are less about just fatherhood, more about change: moving from one phase of your life into another phase. It's a case of saying goodbye. Lots of the songs on the album feel like they're saying goodbye to parts of myself, parts of my life, parts of the person who I was. I don't think it's a record about fatherhood, it's more of a record about the passing of time and what that does to a person."

Even when he was writing Fatherland, Okereke knew that he didn't want to push this record too hard. "Because of the subject matter, I obviously didn't want to do that much promo or travelling," he says. Writing the record marked a radical change in set-up for him: "I didn't even own an acoustic guitar until I started writing the music for this album," he laughs.

In those times when he performs the songs from the record, Okereke plays solo, with just an acoustic guitar. "It's the most naked I've ever felt on stage, but that in itself has been quite exciting to experience," he offers. When not playing shows, though, Okereke has been spending his time parenting; feeling grateful that his "self-employed" status has afforded him so much home time. He's also discovered that, even deep into the 2010s, being a dad at the playground still puts you in the minority. "When I take Savannah to the play-park, it's all just mums. Occasionally you'll see a dad, with a pushchair or a pram, you'll look at each other and smile. Because it's still uncommon, it still looks quite alien to people, to see a father with their baby."

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

Okereke and his partner had spent "two-and-a-half years" planning this pregnancy and, given that it involved a surrogate, there was no element of surprise. In their "elation" at "becoming fathers", during that waiting period the pair had thrown themselves into research, even if Okereke suspected advanced study had its limits. "You can anticipate, do the best preparation, read all the right books, but until you actually meet your child, you don't really know anything about anything," he says. "It's funny: during all this prep, I was always conscious that, despite our best efforts, we were embarking on something that you couldn't actually prepare for."

Fatherland was released in October, which meant, in Australia, it came right at the height (or, perhaps, the nadir) of the plebiscite, and the grand public debate/media circus over basic human rights. Okereke was pleased to hear the Yes vote passed - "you have to believe we're moving forward, not backwards, no matter how disheartened you can feel at the time" - but bristles at any notion that he should be considered some sort of spokesperson for same-sex unions or queer parenthood.

"I don't really feel like I am being an advocate for anything. I'm just living my life, trying to make the best choices that I can," he says. "I think it's quite dangerous when you start thinking of yourself as a role model. Plenty of people in public life have children. Most male musicians who have children don't get asked about being representative of heterosexual fatherhood. I understand why people want me to talk about this, but I don't want to see my entire experience essentially be reduced to something that doesn't figure in my thoughts in my daily life."