In the early hours of April 19 2013, Tamerlan Tsarnaev was killed during a bloody shootout with police at the climax of one of the most intense manhunts in modern American history. Four days earlier, the previously unremarkable and anonymous 26-year-old, along with his younger brother Dzhokhar, had planted two improvised bombs near the finish line of the Boston Marathon, killing three people and maiming 264 others.

After the blast, as the dust settled and the screams began to ring out across Boston's Copley Square, Tamerlan Tsarnaev had been forever changed from an average citizen into a mortal enemy of the State. Gnarled by radicalised Islam, his act of terrorism vilified him not only in life but also in death. Across America, officials from over 120 burial sites refused to allow his body to be buried in their jurisdictions. Protesters picketed funeral homes where his remains were stored, incensed by the notion that a man capable of something so unthinkably abhorrent could still be laid to rest in the earth of a country he had sought to destroy. The argument became a symbolic one of principle and patriotism; this grave could become glorified, a shrine for others seeking to inflict similar atrocities against the American dream. A simple burial was now tantamount, in the eyes of many, to an act of treason.

For Damien Ryan, the artistic director of Sydney-based theatre company Sport For Jove, this recent event shares a striking synergy with a story dating back millennia. In a narrative originating in Greek antiquity, Antigone is denied the right to honour and mourn her dead. Stricken by grief and faced with the prospect of this injustice, she chooses to defy the reigning authority, even though to do so makes her an outcast.

"War used to be a symmetrical thing. Troops lined up against each other; there were rules of engagement. Now, war has become asymmetrical - instead of armies, there are individuals."

For Ryan, the similarities between this story and Tsarnaev's illuminates a facet of this Classical text that has become powerfully relevant in the age of terror. "War used to be a symmetrical thing. Troops lined up against each other; there were rules of engagement. Now, war has become asymmetrical - instead of armies, there are individuals. War can come from a beachfront in Nice or a Lindt Cafe. It can come from anywhere and that raises the temperature of our fear to point that it becomes hatred," Ryan observes. "A terrorist becomes the focal point of that hate, so the question of what we do with the bodies of terrorists becomes about what we do with our anger: do we bury it or do we leave it rotting in the sun?"

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

For his contemporary reboot of Antigone, Ryan has refocused the storytelling, losing the ancient royal dynasty at the heart of the original play. Instead of two warring kings, the story now deals with two diametric ideologies, similar to the polarities of Western democracy and radical Islamic jihad. Stripping back the narrative to its keenest present-day resonances has had a profound effect on the rehearsal process, Ryan explains. "In our version, Antigone's brother has joined ISIS, like so many Australian boys who we have discussed while making this piece. The 15-year-old kid who shot Curtis Cheng outside the Parramatta police station; the boys who have left Melbourne and travelled on boats all the way to Syria to fight against their own country. Talking about these young men in the rehearsal room has made this narrative extremely topical. It's faithful to the source material but also a modern appropriation of this idea: what do we do with the bodies of those we hate?"

Viewing this story through the lens of modern terrorism has muddied the often clear-cut morality of Antigone. Over the centuries, as society has evolved, some of this play's implicit cultural symbolism has given way to a hockey "good versus evil" mentality, positioning the titular heroine as a brave crusader railing against a tyrant. Antigone has become a totem of trailblazing feminism and righteous loyalty, prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice in the service of her cause.

Ryan's account takes a more complicated tack. "Creon [the King who refuses to bury Antigone's brother] is often painted as the villain and Antigone is a Joan of Arc-type figure. I felt it was important both these characters were both right and wrong, because there can be no tragedy unless both parties have legitimate ethical claims to their beliefs," Ryan shares. "A Classical audience, which would have been full of soldiers and those who understood the ramifications, would have heard Creon's words very differently and understood the symbolism of what it means to leave a body rotting on the ground. When Creon speaks about the need for order and discipline after a horrific war, they would have understood the significance of these strong, unambiguous gestures of nation building."

Reimagining Antigone as someone radicalised by grief aligns this usually noble figure with far less endearing motivations. Double-hinging this character poses a challenging question to the audience: should we ever empathise with fundamentalists? "There are moments when she repels us with the intensity of her extremism. She knows the path she treads is dangerous and yet she walks towards her doom with her eyes wide open," Ryan notes. "The ferocity of her certainty is like she's wearing a psychological suicide vest."

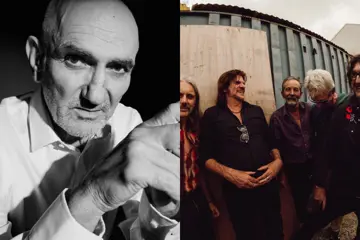

Sport for Jove presents Antigone at the Seymour Centre 6 Oct to 12 Nov