CATS

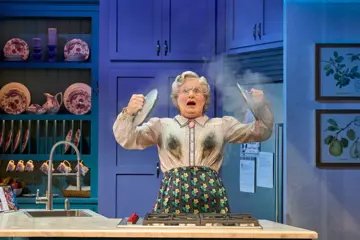

Cats is a calamity. A disaster. $95mil of movie-makin’ trainwreck. In an era of horrible CGI, this may be the most horrible use of CGI ever committed to screen. Andrew Lloyd Webber’s ’80s-defining Broadway-tourist-trap is one of the most profitable cash-cows in stage-musical history, but it seems exceedingly implausible that this long-awaited to-screen translation will be anything but an abject failure. It’s a film you can only recommend to rubberneckers, memelords, and devotees of cinematic schadenfreude. And even they should tread carefully.

For those who witnessed the sheer horror of the Cats trailer, rest assured that it was actually an accurate representation of the movie. All your questions are left unanswered, all your criticisms still apply, all your nightmares remain undimmed.

The story essentially goes like this: we meet a bunch of cats in an alley. They all sing songs introducing themselves, just tune after tune after tune in which they say their ridiculous names over and over like some insecure brand-managing rapper. Then Jennifer Hudson sings Memory twice, hysterically over-emoting to the hilt. Then it ends. It feels scattered, if not butchered; one of this Cats’ many failures likely losing the story, whatever that might be, in editing.

But the #1 reason it’s so bad — like, all-time bad — is the visual presentation of the film, which takes place in some unholy CGI realm that’s hard to believe anyone signed off on (the recent news that a new updated-effects version is being rushed to cinemas strikes me as somewhere between spin-doctoring and turd-polishing). Rather than take the tried-and-traditional theatrical method — have humans wearing cat costumes — the production, helmed by director Tom Hooper (The King’s Speech, Les Misérables, The Danish Girl; aka peddler of A-grade Oscarbait), decides to make these humans-playing-cats bizarre computer-generated concoctions. Behold their “digital fur” technology. And, um, all manner of unholy visions that stem from.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

The effect is somewhere between genuinely unnerving and utterly upsetting. The human faces of the actors feel as if they’re forever ‘floating’, weirdly mapped onto the computer-rendered quasi-cat heads. Though they’re cat-ish, these accursed creatures don’t have the bodies of cats. They have the bodies of people, with opposable thumbs on their human hands, and human feet. The decision to use computer-animation in depicting their forms seems to have been made just so their ears can twitch and their tails can move. But once you start turning these screen concoctions from people-in-costume to rendered pixels, there’s suddenly lots of really weird, creepy decisions to be made.

Like, why are some cats ‘naked’, yet other cats wear suits or fur-coats or shoes? Why is it, even when they’re clothed, only one character feels the need to wear pants? When the Rebel Wilson cat unzips her fur and reveals it to be a onesie, and that her real fur is underneath, does that mean she’s essentially wearing the hide of another cat? Is she the Cats equivalent to Ed Gein?

When these cats are just being played by humans in costumes on stage, of course there are going to be human body-parts involved. But, once they become nightmarish, Dr. Moreau-ish cat/human CGI hybrids, why do some cats have breasts and others don’t? Why does Idris Elba get a jacked cat six-pack? Why does Taylor Swift’s burlesque-routine cat — wearing nothing but a pair of heels — do a va-va-voom titty-shake? The more you think about this, the more horrifying it gets.

And, like, why is scale so wacky? Why are mice — if you think the cats look horrifying, wait ’til you see the mice/human hybrids (and if you think the mice look horrifying, wait ’til you see the cockroach/human hybrids) — so tiny in their paws, yet forks so giant? Sometimes it seems like these cats are supposed to be the size of people, other times 10cm tall. And if we go by the idea that these are cats in a human world — as is suggested when one song finds three cats crashing (literally) a human house — why do all the signs in the background advertise cat-centric products and cat entertainments? What fresh hell does this take place in?

There’s more horrors to recount; probably too many for one review. Wilson’s performance is stupefyingly, facepalmingly bad; one of the worst things I’ve ever seen on a cinema screen. But it may be trumped by James Corden, as a cat in a top hat that has a moustache for some reason. There’s a funky cat who struts around to Nile Rodgers slap-bass and says things like “it’s party time!” and a cat that tap-dances whilst wearing a train-conductor’s hat. Especially bad is the film’s sense of ‘humour’, which involves fat jokes, more fat jokes, pratfalls, male cats being hit in the balls, and plenty of laboured cat/milk sayings.

And for a beloved musical, the songs are pretty fucking awful. There’s generally only two song modes: zany or tragic; the former a forum for endless mugging, the latter overblown belting-out. I came to resent the arrival of each new song, and its attendant horrors. “Who is Old Deuteronomy?” asks the fresh young ingénue cat, at one point. And, what do you know, the bars of the next song start up, and here’s Dame Judi Dench introducing herself as a cat that appears to be wearing a fur-coat made out of its own fur.

But so it goes for this baffling, genuinely terrible movie. It’s a movie that the collective internet knew was going to be a disaster from the second that trailer dropped, but actually sitting down to witness Cats in its entirety is a whole other situation. Or, as I wrote in my notebook, very early into suffering through it: “when the second song starts, I realise I’ve made a horrible mistake.”

★

JOJO RABBIT

What to make of an amiable, almost-family-friendly crowdpleaser about a young German boy desperate to join the Nazi youth, whose best friend is an imaginary Adolf Hitler? Whilst making movie-makin’ comedy out of real-life tragedy should hardly be off cinematic limits, there’s an undeniable difficulty in walking this line. With 2010’s Boy and 2016’s Hunt For The Wilderpeople, Kiwi hero Taika Waititi essentially established the tone that’s at play here: each a tale of boyhood confusion and rebellion that mixes melancholy, mischief, humour, and pathos. With Jojo Rabbit, that’s taken to a bigger scale, both in its historical setting, and in the fact that, following Thor: Ragnarok, Waititi is now a huge, bankable director; the cast filled with Hollywood heavies like Scarlett Johansson, Sam Rockwell, Rebel Wilson, and Stephen Merchant.

Befitting its evocation of childhood, Jojo Rabbit is a film about dress-ups. Its titular character is described as “a 10-year-old kid who likes dressing up in a funny uniform and wants to be a part of a club”, and there’s a notable scene where his mother (played by Johansson), smears soot on her face as a kind of beard, play-acting as the absent father who has disappeared — either abroad or under the ground — during the war. Here, National Socialism is its own kind of grand dress-ups; Germany effectively ‘trying on’ the identity of global conquerors. Here, the Nazis are oft depicted as buffoons, braying and bellicose, willingly throwing themselves into a state of delusion. It’s both a charming device, and one that seems troubling in this particular cultural instant. With the rise of fascism, far-right parties, and neo-Nazis, perhaps this isn’t the best time to go all Hogan’s Heroes.

Once again, Wes Anderson is shown as a huge influence on Waititi. Not just in the symmetrical frames, visual frontality, and comic montages set to pricy classic-rock song placements, but in the love of costume and colour, and the melancholy tone beneath the seemingly-sarcastic presentation. Here, the Nazi Youth seem like the boy-scouts from Moonrise Kingdom, but the moments of tragedy in this tragicomedy — the sight of bodies strung up in public places, reminders that these lulz are playing out against a backdrop of mass genocide — don’t quite carry real sting. Keeping comparisons in the Wes wheelhouse, here the spectre of fascism doesn’t carry the same sense of threat as in The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Jojo Rabbit has been billed, time-and-again, in marketing and on movie poster, as an ‘anti-hate satire’. And the irreverence is reserved for mocking the idiocy of blind adherence to illogical, inhumane beliefs. Its main drama finds its young boy befriending a Jewish girl hiding in the attic, and coming to realise all that he has been taught, his entire worldview, is askance. Whilst early scenes find him fondly hanging with his imaginary Führer (played by Waititi himself, mugging plenty), eventually he says “fuck off Hitler!” and kicks Adolf through a window. It’s a grandstanding repudiation of the forces of hate, but also maybe a little too cute. As is the whole magilla, where the ultimate of human horrors is but the backdrop for a coming-of-age lark. Jojo Rabbit may, in turn, leave many viewers with conflicted feelings. What to make of this film, indeed.

★★★

PORTRAIT OF A LADY ON FIRE

It sounds banal, especially when talking about a modern masterpiece — 2019’s best film, no less — but Portrait Of A Lady On Fire is a film about looking. About the looks between lovers; that magnetic, electric quality. About the way women — especially the women of long ago — look at the world, at the society surrounds them. About the way a painter looks at the subject of a portrait, observing the details that add up to a person. And, most amazingly, in its drama, about how the act of observation can go both ways: just as an artist looks upon a subject, that subject may look right back at them; no passive object of appraisal, but a flesh-and-blood human being who sees the world in their own way, too.

The dramatisation of all this proceeds thus: in the late-18th century, a painter (Noémie Merlant) journeys to an isolated island off the coast of Brittany. There, she’s to secretly work on a portrait of a young lady (Adèle Haenel) due to be wed to a Milanese man she’s never met; the subject refusing to pose for a portrait that will, if ‘approved’ by her suitor, seal a fate she has no control over. As the two head out for walks across the empty, seaside landscape, the painter is to steal discreet looks at her subject, and then work in secret. The narrative changes when the subject dares look back, so much said in the looks between them, which are ever-evolving, filled with complexity.

This is, in such, a film about the female gaze; both in its narrative, and in its making. Writer/director Céline Sciamma previously cast her cinematic gaze upon Haenel with 2006’s Water Lilies. It was Sciamma’s debut film (she followed it with the great Tomboy and Girlhood), and Haenel’s breakout role, acted when she was just 17. Years later, the two entered into a relationship. Without digging — or needing to — for off-screen gossip, much of this history informs the film: A Portrait Of A Lady On Fire a film in which an artist observes Haenel; and one filled with long, lingering looks between lovers.

But, moreso, it’s an impeccably-made piece of cinema. Befitting a film about painting, Sciamma’s framing is precise; and the compositions are filled with all manner of frames-within-frames (and artful play with mirrors). As well as frames, there’s plenty of flames; Sciamma making a recurring visual motif of fire, which, so often, is suggestive of desire, placed in notable proximity to characters, sometimes fluttering, out-of-focus, in the negative-space between her lovers’ gazes. There’s an intricate sound-design, in which the sounds of elemental nature are ever-present, as if pressing in on the emotional lives of people. And whilst there’s no score, there’s incredible use of music in three specific sequences.

One of those comes with the film’s sustained closing-shot — where Haenel, in the crowd of an orchestral performance, silently cries to a performance of Vivaldi whilst the camera presses in — which feels like an instant, all-time-classic even as you’re watching it. It’s set in a years-later coda; a conclusion which only adds endlessly profundity to the piece. Whilst it’s about the connection, and the passion, of a brief, fleeting period of time, Portrait Of A Lady On Fire is ultimately about how those moments live on in memory, and feeling; the flame for a past love something that can still burn, brightly, so many years on.

★★★★★

THE TRUTH

With 2018’s Shoplifters — a movie which continued a career-long history of mixing social-realism with crowdpleasing fable— Hirokazu Kore-eda won the biggest prize in World Cinema, the Palme d’Or at Cannes. The Japanese auteur used his newfound clout, in the wake of the win, to make a film in France, his first-ever movie made outside of Japan. With Catherine Deneuve and Juliette Binoche roped in to star in a mother/daughter drama, he had French cinema royalty on his side. And the resulting movie, The Truth, feels like some kind of valentine to French cinema, given that, within its dramatic narrative, Deneuve plays an aging screen siren working on a new movie, and Binoche not just this siren’s daughter, but a screenwriter. She’s also married to Ethan Hawke, who, in quite a stretch, plays a bad actor.

Deneuve’s character has just published her memoir, full of memories of her (and, in turn, her daughter’s) life, and is also acting in a new high-concept sci-fi saga called Memories Of My Mother. All of this is very symbolically obvious, and even the film’s French title — La Vérité — is pulling cinematic double-duty. There’s evocations of old actors and films, both real and imagined. And so much of the story is set on set; with promotional interviews, press conferences, table reads, and rehearsals all given screen-time.

It’s pleasant, non-threatening stuff; even its great dramatic revelations, about a long-lost young actress who served as Binoche’s mother-figure in her childhood, seeming like pretty standard stuff. The themes are spoken aloud — “you can’t trust memory, even for acting,” Deneuve says, “memories come and go” — more than they’re explored or entrenched in the narrative. And, like so many movies about making movies, you have to question why this story is being told, whether there was a searing need to bring it to screen. But maybe Kore-eda doesn’t even think there was. At The Truth’s Melbourne premiered, he introduced the film by telling viewers it was “to take in quite casually”.

★★1/2

SORRY WE MISSED YOU

Ken Loach is 83 years old. He’s made 25 feature films. Kes, his classic, came out 50 years ago. But time has hardly wearied him. Where many directors deliver careers full of peaks and valleys, failures and returns-to-form, Loach’s filmography has been almost unrelentingly stellar. Outside of Kes, in its landmark status, favourite Loach films and eras are up for debate, with no wrong answer. I’m particularly fond of the back-to-back of Ae Fond Kiss… (2004) and The Wind That Shakes The Barley (2006), but am hardly going to fight someone who loves Land And Freedom (1995) or The Navigators (2001) or his last film, 2016’s acclaimed I, Daniel Blake.

Red Ken is still, evidently, angry; full of horror and fury at the state of the contemporary world. After decades of kicking against the pricks, delivering social-realist portraits of the lives of the downtrodden working class — of making films about unions and strikes and activists, about those undone by the system or at the frontlines of history — he’s still bringing to screen trenchant, topical themes. A Loach movie is, usually, filled with humour and horror, tragedy and a sense of undimmed humanity; these rousing portraits of dire straits designed to shake arthouse audiences from their complacency.

Sorry We Missed You feels like classic Loach, but it’s also a film of the contemporary moment. In it, he dramatises the horrors of the gig economy and the zero-hour-contract labour-force. Kris Hitchen plays a struggling father-of-two who becomes a self-employed, independent-contract delivery-van driver; and thus slave to the inhuman dictates of a contractor who doesn’t care about his wellbeing, emotional state, familial situation, or decaying mental health. In turn, this has a hugely deleterious effect on his family, and his family life; things going from bad to worse, with no hope on the horizon.

It’s a memorable, meaningful portrait of modern employment as a form of indentured wage-slavery; the banality of the office-space seeming charmingly retro in the face of a surveillance-state operation wholly beholden to the dictates of the clock. Here, Loach and his long-time writer, Paul Laverty, put a human face on those who suffer for the dictates of the free-delivery marketplace. In an age where contemporary employment can be symbolised by the inhuman dictates of the Amazon warehouse, Sorry We Missed You is all too timely. For all his advanced years, Loach has no interest in venerating the past; instead, he continues to interrogate the injustices of the present.

★★★★