Johnny Marr

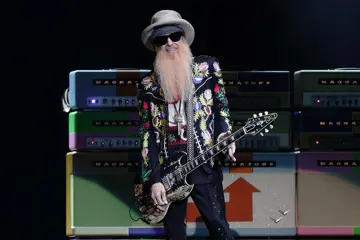

Johnny MarrFor decades Manchester-bred Johnny Marr has been acknowledged as a shining light in the long lineage of legendary UK guitarists that stretches back to the very foundations of rock'n'roll, but until recently he's also been considered something of a professional sideman.

Following the five incredibly fertile years between 1982 and 1987 that he spent co-writing and playing on The Smiths' catalogue of oft-forlorn love songs – a relatively fleeting period during which he inherently ceded attention to the ludicrously enigmatic Morrissey, and which still looms large over his life today – Marr has spent his career flitting between an incredibly diverse array of projects, never coming even close to outstaying his welcome. Whether adding his distinctive chops to already functioning bands such as The Pretenders (briefly), The The, Modest Mouse and The Cribs, or starting projects from the ground up such as Electronic (which he helmed with New Order's Bernard Sumner), if Marr wasn't on the road or recording with one of these acts he'd just as likely be found in the studio helping out a slew of equally high-stature artists such as Billy Bragg, Beck, Talking Heads and Pet Shop Boys. He became, in fact, a veritable gun for hire who was happy to share (or eschew) the limelight as long as he was connecting with the music that he was working on and enjoying the company of those he was working alongside.

Only once has Marr really stood front and centre for any extended period of time, when he pulled together his Johnny Marr & The Healers project at the turn of the millennium. While they only released one album (2003's Boomslang), The Healers still exist to this day (in various guises) during gaps in Marr's busy dance card, and when he left The Cribs in 2011 the tunes he began assembling were ostensibly for another Healers album. Yet fate intervened as it so often does, and when a committee of people in his inner sanctum conspired that this should in fact be a solo project, The Messenger was born – the first ever Johnny Marr solo album dropping some 35 years after he first picked up a guitar in anger.

“It happened pretty quickly, after only a couple of weeks of writing,” Marr smiles. “I was going into the studio every day with my friend who's my co-producer, Doviak, and about two weeks into it I was writing pretty much a song a day, and he just said to me, 'This should be a solo record!' I'd never really considered doing a solo record, partly because I thought the name The Healers was such a good name, but I lived with his idea for a week or two and I talked to people around me, and everybody agreed that I should just make it a solo record.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

“Once I was alright with the idea it became more personal. The songs aren't particularly about me exposing the depths of my soul, god forbid – the world has got enough of that kinda stuff – but knowing that it was going to have my name on it meant that it was on my toes, and that it was about my worldview and I was going to be the band leader and all of that.”

The Messenger has an angular, post-punk vibe which verges on new wave at times, not surprising when you consider that this was the obsessive music fan Marr's musical bread and butter before he found fame and (one presumes) fortune in The Smiths.

“It wasn't that I was out to copy a style, just that I wanted to play music like I was playing when I left school,” he reflects. “Inevitably you sound like you do now, and there's sounds on there that are obviously things that I learned from being in Electronic, or things that I learned from being in The Smiths, or things that I learned from Modest Mouse or The The or whatever, [but other things] sound like the songs that I was writing when I was a youngster. I really wanted to reconnect with my roots and what influenced me, and when I left school that was post-punk. What I was doing myself when I formed The Smiths was the next thing after that, which I guess if we're going to think about labels was probably what was first called 'indie' – although that means something else entirely now – but [for The Messenger] I wanted to make music that inspired me when I was younger and that I'd like to play guitar and sing on, and that was I guess the 'new wave'.”

In his Smiths co-writes it's easy to picture Marr conjuring the vibrant riffs and music while Morrissey penned the dramatic, disaffected words, but The Messenger proves indubitably that Marr can more than look out for himself in the lyrical stakes.

“I went into the record really determined not to be baring my soul or doing anything too earnest, because frankly I find so much of that has crept into rock music and I can't stand it! There's this tendency to take the easy route lyrically and come up with stuff about, 'Our souls were flying through the sky, we will all be together', against this imagined adversity that 30,000 people in a stadium all seem to have going against them – what is this adversity that we all have to put our arms around each other and stand against? I don't get it. I grew up in a time when people like Brian Eno were making solo records and Wire and Buzzcocks and they weren't singing about that kind of nonsense, so I wanted to avoid that kind of feel at all costs.

“I wanted to look outwards; I was just a bit tired of society and everyone being so obsessed with inward looking. I wanted to make a record that sounded good in the daytime, and made you feel good on your iPod on the way to school or on your way back from work or on your lunch-hour, so I felt that it was important that the lyrics didn't bring that down. I've been touring a lot over the last five years with The Cribs and Modest Mouse and seeing a lot of towns and cities and buildings and the stories behind those and market forces and things that go on in cities and societies, so I'm interested in those things really, but I think it's important if you make some commentary that it doesn't come across as a complaint or some whinge.

“In the case of that opening track The Right Thing Right, I'm making a commentary that we're all under the effect of very, very crass and powerful and skilful market force manipulation and commercialisation and advertising, but I didn't want my audience to feel that I was singing about victimisation; it's saying, 'Because I'm observing it I'm aware of it and it hasn't got its hooks in me'. In a way it's a celebration of the 'fuck you' – 'I'm aware that I'm a target but you won't catch me'.

“My audience is quite diverse – there are people who have followed me over the years and probably grew up with me when they were in college and gone through life and they're still with me, and also there are a lot of younger people who come to see me who got to know me though Modest Mouse, say, and I try to find the common bond between those two groups. I found that I'd been thinking about some of the younger people who'd been coming to see me and how there's a wisdom and ability that teenagers have to see through the bullshit – they know when a teacher's patronising them, or they know when somebody's trying to get them to watch some crappy film or trying to make them a target – but it takes adults to go through their 30s and 40s to regain that wisdom. So I just had this idea that that's where both sides of my audience unite, this observation of the bullshit – it's like a celebration of viva la resistance – so if there is an overlying arc to the way I write my lyrics it's that if you're going to make a commentary, don't bring the music down with a complaint. I'm not interested in sitting in the corner of a room with the lights off saying, 'Nobody understands me'.”

Is Marr speaking from personal experience in that regard?

“Maybe, I don't know,” he chuckles. “People from my past have mastered that already I think.”